LIBRARY

UE: POL 110-HA: Democracy in Troubled Times

- Course Introduction

- Is Democracy in Decline?

- Democracy in Ancient Athens

- Roman Republic

- American Revolution

- French Revolution

- Tocqueville - Democratic Defects

- Tocqueville - Democratic Remedies

- American Civil War

- Rise of Democracy in Great Britain

- British Empire to Commonwealth

-

American Century <20th Century>

- Overview - FDR's New Deal and the Economy

- VIDEO RESOURCES - American Century

- ONLINE TEXTS - American Century

- FDR & the New Deal

- Social Security -- the cornerstone of the New Deal

- Contemporary Critics of the New Deal

- FDR & World War II

- LBJ and the Great Society

- Thatcher-Reagan Reaction

- Big Ideas, Essential Questions, and Higher Order Thinking

- Communism and Fascism in the 20th Century

- Presidential Democracy in France's 5th Republic

- Collective Security & World Organizations

- Mass Movements Abroad

- Contemporary Challenges to Western Democracy

- For Further Research

-

Spartan Republic

Overview - FDR's New Deal and the Economy

Franklin Roosevelt’s legacy, as the longest serving U.S. President, can be broken into two parts: (1) the various efforts made to overcome the economic collapse of the Great Depression, collectively called the New Deal, and (2) the struggle to engage against fascism in Europe and to repel an oligarchic, militarized Japan in the Far East.

Roosevelt's New Deal brought into high relief the impact of historical economic forces at work within democracy, namely, the nationalization of the economy (particularly large scale manufacturing), the rise of industrial labor, and the importance of world trade and global markets. The New Deal envisioned the national government effectively operating to smooth the transition to a modern economy (by preventing market manipulation and arbitrating industrial strikes), to protect and empower workers (by organizing the workforce and providing jobs if necessary), and to nurture and expand international commerce. In so doing, the New Deal ushered in the much maligned age of “big government”.

In the 1960’s, Lyndon Johnson resurrected the impulse of FDR’s New Deal as his own “ Great Society” in an effort to promote civil rights (particularly with regard to race relations) and economic opportunity (as part of the unfortunately named ”War on Poverty”). At the same time, LBJ used his expanded presidential powers to send American forces abroad to prevent the spread of communism into Southeast Asia.

In a way, the Reagan Revolution of the 1980’s may be understood as a reaction to LBJ’s Great Society, with its effort to shrink the national government, promote free enterprise, and return to “traditional values”. Thus, the economic tug-of-war between the current Democratic and Republican parties can be seen as a reflection of the democratic debate over the appropriateness and efficacy of Roosevelt's New Deal.

Essential Questions:

- Was the Great Depression the result of unregulated, unbridled capitalism?

- Was FDR’s New Deal an attempt to impose socialism on the U.S.?

- Do the practices of capitalism and free trade necessarily lead to a democratic society and government?

Copyright © 2013 - Hudson Reynolds, Ph.D.

VIDEO RESOURCES - American Century

-

The Great Depression -1/5 - BBC [57:00]

-

The New Deal -- BBC History [19:01]

-

Archie Bunker versus Maude over FDR (classic comedy) [3:36]

-

Reagan: The American Experience [2 hrs 21 min]

-

Ronald Reagan [1 hr 36 min]

-

Margaret Thatcher: the Woman Who Changed Britain [49:22]

-

Margaret Thatcher -- The Making of ... 1/8 [50:48]

-

Margaret Thatcher on "The Downing Street Years" [58:18]

-

Christopher Hitchens on Thatcher-Reagan [1 hr 26 min]

ONLINE TEXTS - American Century

FDR & the New Deal

The Great Depression

Conventional wisdom places the beginning of the Great Depression on “Black Tuesday” October 29, 1929, but the factors undermining the economic stability of American and world markets had been in play for some time.

One of those factors was a lack of diversification in the American economy throughout the 1920’s. American prosperity had been built on a few core industries, most noteworthy automobiles and construction. As the 1920’s progressed, market saturation began to take hold and automobile and construction expenditures began to drop dramatically. In addition to the declining demand for products, purchasing power began to skew against those at the lower end of the economic ladder. As demand for products decreased, so did wages - especially for farmers and factory workers. More and more consumers found themselves unable to afford the goods and services the economy was producing. This resulted in even less demand and sparked layoffs and factory shut downs.

Yet another factor contributing to the economic woes of the nation was the dubious debt structure of the economy. Farmers who traditionally live on or near the edge of economic prosperity, were being hit with the double whammy of declining crop prices and a continuing drought that was literally turning their land to unuseable dust. Crop prices were too low to cover the fixed costs of machinery, taxes, mortgages and other debts. By 1933, nearly 45 percent of farms were behind in their mortgage payments and faced foreclosure. Many farmers in the southwest region of the country that had come to be called the Dust Bowl simply abandoned their farms. These “Arkies” and “Oakies” loaded up their families and whatever possessions they could carry and headed west.

A final factor came from beyond our borders. When World War I finally concluded, the Allied nations of Europe owed American banks huge sums of money. With the European economies in shambles, not even the victorious countries were able to make their payments to American banking institutions. They had insisted on reparations from the defeated nations in hopes of using those resources to repay their American creditors. The defeated nations were even less able to muster the necessary funds. American banks refused to forgive the debts, but they did allow European governments to take out additional loans to pay down the original debts. This created a dangerous cycle of paying debts by incurring still more debt.

By the end of the 1920’s, the American economy was beginning to weaken due to the factors mentioned above. In an effort to protect American manufacturing, protective tariffs were put in place making it more and more difficult for European goods to enter the United States, and many soon defaulted on their loans bringing about a world wide economic crisis.

<http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/education/resources/pdfs/socialsecurityguide.pdf> (10/13/13)

Birth of the "New Deal"

In early 1933 nation needed immediate relief, recovery from economic collapse, and reform to avoid future depressions, so relief, recovery and reform became Franklin D. Roosevelt`s goals when he took the helm as president. At his side stood a Democratic Congress, prepared to enact the measures carved out by a group of his closest advisors — dubbed the “Brain Trust” by reporters. One recurring theme in the recovery plan was Roosevelt’s pledge to help the “forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.”

The concepts that became the New Deal had been discussed in earlier years but without effect. The statement by National Catholic War Council in 1919, drafted by Father John A. Ryan, contained recommendations that would later be regarded as precursors of the New Deal.

The concepts that became the New Deal had been discussed in earlier years but without effect. The statement by National Catholic War Council in 1919, drafted by Father John A. Ryan, contained recommendations that would later be regarded as precursors of the New Deal.

The term "New Deal" was coined during Franklin Roosevelt’s 1932 Democratic presidential nomination acceptance speech, when he said, "I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people." Roosevelt summarized the New Deal as a "use of the authority of government as an organized form of self-help for all classes and groups and sections of our country."

The exact nature of Roosevelt`s intentions was not clear during the campaign, although his philosophy was set out in an address that he gave at the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco on September 23:

The government should assume the function of economic regulation only as a last resort, to be tried only when private initiative, inspired by high responsibility, with such assistance and balance as government can give, has finally failed. As yet there has been no final failure, because there has been no attempt, and I decline to assume that this nation is unable to meet the situation.

At his inauguration in March 1933, Roosevelt declared in his lilting style, "Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is, fear itself — needless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance." In his first 99 days, he proposed, and Congress swiftly enacted, an ambitious "New Deal" to deliver relief to the unemployed and those in danger of losing farms and homes, recovery to agriculture and business, and reform, notably through the inception of the vast Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The New Deal effects would take time; some 13,000,000 people were out of work by March 1933, and virtually every bank was shuttered.

The New Deal programs were born in Brain Trust meetings prior to Roosevelt’s inauguration, and also were a grateful nod to Theodore Roosevelt`s "square deal" of 30 years earlier. Members of the group included Raymond Moley, an American journalist and public figure; Rexford Tugwell, Adolf Berle of Columbia University, attorney Basil O`Connor, and later, Felix Frankfurter of Harvard Law School. Many of Roosevelt`s presidential campaign advisors continued to counsel him after he was elected, among them Berle, Moley, Tugwell, Harry Hopkins, and Samuel I. Rosenman; but they never met again as a group after his inauguration.

<http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1851.html> (10/13/13)

What exactly was the "New Deal"?

The New Deal was the set of federal programs launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt after taking office in 1933, in response to the calamity of the Great Depression. It had four major goals and achievements:

• Economic Recovery: The New Deal stabilized the banks and cleaned up the financial mess left over from the Stock Market crash of 1929. It stabilized prices for industry and agriculture, and it aided bankrupt state and local governments. And it injected a huge amount of federal spending to bolster aggregate incomes and demand.

• Job Creation: One in four Americans was out of work by 1933. The New Deal created a number of special agencies that provided jobs for millions of workers and wages that saved millions more in their desperate families. It also recognized the rights of workers to organize in unions.

• Investment in Public Works: The New Deal built hundreds of thousands of highways, bridges, hospitals, schools, theaters, libraries, city halls, homes, post offices, airports, and parks across America—most of which are still in use today.

• Civic Uplift: The New Deal touched every state, city, and town, improving the lives of ordinary people and reshaping the public sphere. New Dealers and the men and women who worked on New Deal programs believed they were not only serving their families and communities, but building the foundation for a great and caring society.

In less than a decade, the New Deal changed the face of America and laid the foundation for success in World War II and the prosperity of the postwar era – the greatest and fairest epoch in American history.

<http://livingnewdeal.berkeley.edu/resources/what-was-the-new-deal> (10/13/13) ?

The "Hundred Days"

The president called a special session of Congress on March 9. Immediately he began to submit reform and recovery measures for congressional validation. Virtually all the important bills he proposed were enacted by Congress. The 99-day (March 9-June 16) session came to be known as the "Hundred Days."

On March 12, 1933, Roosevelt broadcast the first of 30 "fireside chats" over the radio to the American people. The opening topic was the Bank Crisis. Primarily, he spoke on a variety of topics to inform Americans and exhort them to support his domestic agenda, and later, the war effort. During Roosevelt`s first year as president, Congress passed laws to protect stock and bond investors.

Among the measures enacted during the first Hundred Days were the following:

The “Second Hundred Days"

Congress also enacted several important relief and reform measures in the summer of 1935 — sometimes called the Second Hundred Days.

During the Second Hundred Days, those measures enacted included:

Following Roosevelt`s lead, the government launched a relief program, the Civil Works Administration (CWA), in winter 1933-1934. The CWA provided funds to such authorities as mayors and governors for public projects including road, bridge, and school construction, park restoration, and others. Critics castigated the CWA as make-work, much of it useless.

After a few months, Roosevelt terminated the CWA, but other programs enjoyed longer lives. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) lasted from 1933 until 1942. Its members produced notable and lasting results with flood control, soil conservation and forestry programs. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was established in 1935 to provide work for the unemployed. Between that year and 1941, the WPA employed an average of two million people a year. The WPA went on to spend billions on reforestation, flood control, rural electrification, water works, sewage plants, school buildings, slum clearance, student scholarships, and other projects. Their crowning achievement came in the completion of the Bonneville Dam on the Columbia in 1937.

Labor Legislation

The New Deal also greatly influenced the American Labor Movement, especially through the following legislation:

- Through the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 the National Recovery Administration (NRA) came into being. The NRA attempted to revive industry by raising wages, reducing work hours and reining in unbridled competition. Portions of the NRA were ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935; however, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which was the second part of the NRA, was allowed to stand. The majority of its collective bargaining stipulations survived in two subsequent bills. The NRA — a product of meetings among such “Brain Trust” advisors as Raymond Moley, big business leaders, and labor unionists — illustrated Roosevelt`s willingness to work with, rather than against, business interests.

The U.S. government could reach out in the widest way to alleviate human misery — such was an assumption that underlay the New Deal. Beginning in 1935, Congress enacted the Social Security Act of 1935 (and later amendments) that provided pensions to the aged, benefit payments to dependent mothers, crippled children and blind people, and unemployment insurance. Small businesses, homeowners and the oil and railroad industries were given help by other legislation.

Summary

The experiment of the New Deal yielded varied results. Some programs were nearly universally applauded such as the CCC, TVA, or the FDIC. Others such as the NRA were attacked in the media or overturned in the courts. Still others such as Social Security have become so interwoven in our social and political fabric that it is difficult to imagine a time when they did not exist. Regardless of the fate of the individual programs, the fact remains that the New Deal forever changed the political, social, and economic landscape of the United States. Historians and scholars continue to debate just how successful the relief, recovery and reform efforts of the New Deal programs were and their lingering impacts today.

<http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1851.html> (10/13/13)

Top Ten "Alphabet" Programs of the New Deal

1. CCC - Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps was created in 1933 by Franklin D. Roosevelt to combat unemployment. This work relief program had the desired effect and provided jobs for many Americans during the Great Depression. The CCC was responsible for building many public works and created structures and trails in parks across the nation.

2. CWA - Civil Works Administration

The Civil Works Administration was created in 1933 to create jobs for the unemployed. Its focus on high paying jobs in the construction arena resulted in a much greater expense to the federal government than originally anticipated. The CWA ended in 1934 in large part due to opposition to its cost.

3. FHA - Federal Housing Administration

The Federal Housing Administration was a government agency created to combat the housing crisis of the Great Depression. The large number of unemployed workers combined with the banking crisis created a situation in which banks recalled loans. The FHA was designed to regulate mortgages and housing conditions.

4. FSA - Federal Security Agency

The Federal Security Agency established in 1939 had the responsibility for several important government entities. Until it was abolished in 1953, it administered social security, federal education funding, and food and drug safety.

5. HOLC - Home Owner's Loan Corporation

The Home Owner's Loan Corporation was created in 1933 to assist in the refinancing of homes. The housing crisis created a great many foreclosures, and Franklin Roosevelt hoped this new agency would stem the tide. In fact, between 1933 and 1935 one million people received long term loans through the agency that saved their homes from foreclosure.

6. NRA - National Recovery Act

The National Recovery Act was designed to bring the interests of working class Americans and business together. Through hearings and government intervention the hope was to balance the needs of all involved in the economy. However, the NRA was declared unconstitutional in the landmark Supreme Court case Schechter Poultry Corp. v. US. The Supreme Court ruled that the NRA violated the separation of powers.

7. PWA - Public Works Administration

The Public Works Administration was a program created to provide economic stimulus and jobs during the Great Depression. The PWA was designed to create public works and continued until the US ramped up wartime production for World War II. It ended in 1941.

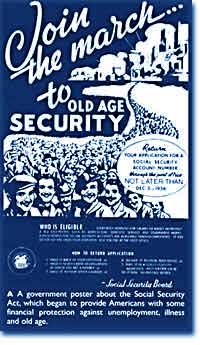

8. SSA - Social Security Act

The Social Security Act was designed to combat the widespread poverty among senior citizens. The government program provided income to retired wage earners. The program has become one of the most popular government programs and is funded by current wage earners and their employers. However, in recent years concerns have arisen about the viability of continuing to fund the program as the Baby Boom generation reaches retirement age.

9. TVA - Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority was established in 1933 to develop the economy in the Tennessee Valley region which had been hit extremely hard by the Great Depression. The TVA was and is a federally owned corporation that works in this region to this day. It is the largest public provider of electricity in the United States.

10. WPA - Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration was created in 1935. As the largest New Deal Agency, the WPA impacted millions of Americans. It provided jobs across the nation. Because of it, numerous roads, buildings, and other projects were completed. It was renamed the Works Projects Administration in 1939. It officially ended in 1943.

<http://americanhistory.about.com/od/greatdepression/tp/new_deal_programs.htm> (10/13/13)

Social Security -- the cornerstone of the New Deal

|

|

|

It is America’s biggest social program, providing benefits to over 52 million people. It is one of the largest single items in the federal budget, representing over 20 percent of all spending. And though, in 2011 we marked its 75th anniversary, its future commands national attention. It is Social Security. The crown jewel of the New Deal, Social Security is FDR’s greatest legacy to the nation. Roosevelt called it “our plain duty” — a basic obligation Americans owe to one another. “He always regarded the Social Security Act as the cornerstone of his administration,” Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins recalled, “and . . . took greater satisfaction from it than from anything else he achieved on the domestic front.”

Almost half of America’s senior citizens could not support themselves. Millions lived in poverty. Most had no access to private pension plans and the limited state-run programs that existed had paltry benefits and stringent age and residence requirements. Most older Americans worked until they dropped or were fired, sought help from family or charities, and tapped whatever savings they had. But in the depths of the Great Depression, jobs and family assistance became harder and harder to secure. And, the life savings of millions disappeared when thousands of banks collapsed.

The unemployed also lived on the razor’ s edge. In 1933, one in four workers was out of work. With no federal safety net of unemployment benefits, a layoff notice could swiftly lead to poverty. A sudden illness or accident or the death of a breadwinner could bring disaster just as quickly.

When the Great Depression struck, there was no federal social safety net for the elderly and the unemployed. State and local government provided little aid. Family resources and charities were stretched to the breaking point. Older job seekers struggled with the added burden of age discrimination.

As the crisis deepened, populist movements sprang up, demanding government action to ensure economic security. Louisiana Senator Huey Long championed his popular “Share Our Wealth” program, promising steep taxes on the rich to fund pensions and a guaranteed annual minimum income of $2500 ($40,000 in 2010 dollars) for everyone. In California, an unemployed 66-year-old doctor named Francis Townsend devised the Townsend Old Age Revolving Pension Plan. He proposed that the federal government provide a $200 a month pension (around $3300 in 2010 dollars) to every person age 60 or older. The pensions would be funded by a national sales tax.

Pensioners had to spend their monthly checks within 30 days. Townsend argue d this would revive the economy by stimulating consumer spending. Critics said it would simply transfer purchasing power from the young to the old, while doubling the national tax burden. Still his movement spread like wildfire. By 1935, thousands of Townsend Clubs boasted over two million members.

Franklin Roosevelt was the first sitting president to support government sponsored old age, unemployment, and health insurance. FDR wanted to enact a national program to address the broad problem of economic insecurity. But he recognized he would face political, economic, and constitutional challenges. Taking office at the lowest point of the Great Depression, the new President chose to delay tackling long-term economic security as he focused on battling the immediate crises of hunger and joblessness.

While Roosevelt delayed, he was pushed to act by his Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins. The first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet, Perkins was deeply committed to creating a permanent social safety net for Americans. FDR also faced pressure from the fast-growing national movement for old age pensions founded in 1933 by Dr. Francis Townsend. Millions of Americans signed petitions supporting Townsend’s pension plan.

On June 29, 1934, FDR acted. He issued an executive order creating a cabinet level Committee on Economic Security to prepare legislation for Congress. Its chair was Frances Perkins. On January 15, 1935 the Committee on Economic Security presented its final report to President Roosevelt. Two days later, FDR unveiled the Social Security program and sent it to Congress. Though Democrats had a nearly three to one majority in the House and Senate, Congressional passage was not swift or easy. At key points the bill threatened to become unraveled or postponed. Congress made significant changes. Most importantly, it scaled back coverage, dropping many large labor categories, including farm and domestic workers. Though others in the administration objected, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau had told Congress it would be difficult to collect payroll taxes from such workers.

In the House many were indifferent to a program that promised payroll taxes in the short-term and only limited benefits until 1942. Some favored more radical proposals like the Townsend Plan. A March 30, 1935 New York Times headline noted “Hopes Are Fading For Security Bill.” In April, FDR took action. He called House leaders to the White House and urged them to pass the Act as a matter of loyalty to him. On April 19 the House approved the bill 372 - 33, with strong bipartisan support. In late April, the President touted Social Security during a Fireside Chat to the nation. In the Senate, the bill’s supporters fought an effort to let businesses with pension plans opt out of Social Security. On June 19, a bi-partisan majority in the Senate passed the measure 77 - 6. A Senate-House committee worked out differences between the two versions of the bill and, in early August, Congress sent the Social Security Act to the President.

On August 14, 1935 legislators and advisors crowded into the White House Cabinet Room to witness the signing of the Social Security Act. News photographers and film crews recorded the moment for history as FDR put his signature on the bill. Standing directly behind the President was the person most responsible for it — Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins. After signing the Act, the President read a short statement. “We can never insure one hundred percent of the population against one hundred percent of the hazards and vicissitudes of life,” he observed. "But we have tried to frame a law which will give some measure of protection to the average citizen and to his family against the loss of a job and against poverty-ridden old age.” The headline in that day’s Washington Post read “New Deal’s Most Important Act.” Few today would disagree.

Social Security instantly became America’s biggest social program. Yet, ironically, a program now deemed by some to be too large to keep its promises was criticized in 1935 for being too small. Initial Social Security benefits were much lower than today and the program covered only 60 percent of workers. Vast groups — most significantly millions of farm and domestic workers — were excluded. Because Hispanics and African Americans filled a large percentage of these jobs, they were disproportionately affected. The system also reflected traditional views of family life.Many jobs categories dominated by woman were not covered. Women generally qualified for insurance through their husbands or children.

Seventy-five years after its creation, Social Security is widely popular. But it is also controversial. In recent years, its long-term financial viability has been debated, with critics echoing complaints first raised during the 1930s. Social Security’s defenders criticize Congress’s use of money from the Social Security Trust Fund for other purposes and argue that the system’s solvency can be assured with shared economic sacrifice.

Stark demographic and fiscal trends demand the nation’s attention. Without action, the Social Security Trust Fund will be empty in 2037. Ultimately, the question today is the same one the nation has faced since 1935. Is Social Security still “our plain duty”?

<http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/education/resources/pdfs/socialsecurityguide.pdf> (10/13/13)

Contemporary Critics of the New Deal

As Roosevelt pointed out, the New Deal wasn't so new. He claimed inspiration from the progressivism of Woodrow Wilson, under whose administration Congress created the Federal Reserve System, lowered tariffs, and tried to legalize unions. Republicans supporting him cited Roosevelt's cousin-uncle Theodore, under whose administration Congress began to regulate corporate accounting and passed truth-in-advertising and pure-food laws. Farm supporters of the New Deal drew on the decades-old tradition of populism, which opposed the gold standard and demanded that government assist rural residents as much as it assisted railroad corporations. What was new in 1932 was a basket case economy with 23 percent unemployment, offering the possibility of getting these American traditions together to fuel a national majority coalition—which is what the New Deal did.

Despite its deep American roots and its popularity across class, regional, religious, racial, ethnic, and to a degree even party lines, the New Deal never lacked critics. They came mainly from the corporate boardrooms and the white-shoe law firms. They could not deny the New Deal's popularity, so they challenged its Americanness. They claimed, as the attorney Frederick Wood did in 1935, that Roosevelt aimed at "some form of national socialism—whether Soviet, Fascist, or Nazi." Some duPont executives, annoyed that the New Deal was raising wage rates for black workers, created the American Liberty League for "encouraging people to get rich" instead of supporting Roosevelt. They made the 1936 election a referendum on the New Deal.

Roosevelt won this referendum by a record majority. He appealed most to the poor—pollsters found Roosevelt garnered 76 percent of the lower-income vote. But he won more than 60 percent of middle-income votes, and even 42 percent of upper-income votes.

If the New Deal survived that test, so did the white-shoe critiques. Today, Grover Norquist complains the New Deal was "un-American." And like-minded Amity Shlaes says in the Wall Street Journal that she wants "[t]o write sympathetically about the Liberty Leaguers." Which she does, in her new book, The Forgotten Man. Despite its subtitle, it's less "a new history of the Great Depression" than what Shlaes says it is: a resurrection of the duPont critique of the New Deal, circa 1935. The New Deal was un-American, she argues, and bad for business.

The New Deal did bear some relation to European welfare states, but it was an uneasy one. Consider Social Security, which would have been simpler had the Democrats written a European-style law, using general funds to support retirees. Instead, out of an American conviction that we "mustn't have a dole," Roosevelt insisted on a contributory scheme which has required repeated tweaks. Shlaes never makes a clear argument about New Dealers' relationship to European politics, center or left. She writes first that "the problem of the New Dealers on the left was not their relationship with Moscow or the Communist Party in the United States, if indeed they had one," but then gives a chapter to discussions of various leftish reformers' interest in the Soviet Union, without showing that this significantly affected New Deal policy.

As for being bad for business: The greatest knock on the New Deal is it did not end the Great Depression. The war did that. Open the authoritative reference work Historical Statistics of the United States and you will find that the unemployment rate did not return to its 1929 level until 1943.

But if the New Deal did not end the Great Depression, was it doing some good? Historical Statistics of the United States says yes: Except in the 1937-38 recession, unemployment fell every year of the New Deal. Also, real GDP grew at an annual rate of around 9 percent during Roosevelt's first term and, after the 1937-38 dip, around 11 percent.

So on the numbers, the U.S. economy improved briskly during the New Deal. Things that are moving quickly and in the right direction, but still haven't reached their destination after a while, are things that have a long way to go—which is true of the U.S. economy recovering from 1932. Historians disagree on which part of the New Deal most encouraged economic growth, but at the least the New Deal did not prevent this recovery.

-- Eric Rauchway, the author of Blessed Among Nations: How the World Made America and The Great Depressionand the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction, is professor of history at the University of California, Davis.

<http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/books/2007/07/fdrs_latest_critics.html> (10/13/13)

FDR & World War II

World War II was the most devastating war in the history of mankind. Between 1939 and 1945, an estimated 60 million people were killed in fighting that literally spanned the globe. Democracy was threatened in every corner of the world and its survival hung in the balance. Franklin Roosevelt understood the importance of this immense challenge and possessed an instinct for power and a willingness to exercise it.

With America’s entry into the war after the December 7th surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt moved aggressively to centralize strategy and high command in the White House. He organized the work of war mobilization and military information gathering so that he could closely monitor and direct events himself. He set priorities and focused attention on the goal of total victory. Under his direction, the government assumed unprecedented powers over the economy. Federal defense spending skyrocketed and the public was mobilized to pay the bill. Millions of Americans began paying federal taxes for the first time. War bond sales raised billions of additional dollars. To control inflation, the government put limits on wages, prices, and rents. And to conserve scarce goods for military use, products ranging from gasoline to sugar were rationed.

Roosevelt's military advisers ranged from the anonymous to the flamboyant. The President employed his formidable political skills to manage relationships with, and among, them. Together, he and his lieutenants virtually created the modern American military. The armed services grew from an unprepared force of 334,473 active duty personnel in 1939 to 12,123,455 in 1945. The army and navy expanded and modernized and, with FDR's endorsement, American air power increased dramatically. The President also supported new agencies like the Office of Strategic Services (precursor to the CIA) and the Office of Scientific Research and Development.

Roosevelt held the key position in a wartime coalition of 26 nations he called the “United Nations.” He, Josef Stalin, and Winston Churchill comprised the “Big Three” at the heart of this coalition. But, as the war progressed, FDR increasingly acted as the group's ultimate broker and decision-maker. Throughout the war, the President emphasized the importance of coalition-building. Diplomacy, as much as military strategy, became a hallmark of his wartime leadership.

To fight a global war, the United States needed to mobilize its entire population along what became known as the “Home Front.” Children organized scrap drives to salvage rubber and metal for war industries, while their parents joined civil defense units, planted Victory Gardens, and purchased war bonds. Government propaganda reminded people to report suspicious activity. Americans joined the Red Cross, the USO, and other service organizations. This enormous national effort touched nearly every aspect of American life and set in motion economic and social forces that would reverberate for decades.

LBJ and the Great Society

Lyndon Johnson, a Texan who was majority leader in the Senate before becoming Kennedy's vice president, was a masterful politician. He had been schooled in Congress, where he developed an extraordinary ability to get things done. He could plead, cajole or threaten as necessary to achieve his ends. As president, he wanted to use his power aggressively to eliminate poverty and spread the benefits of prosperity to all.

Johnson took office determined to secure the measures that Kennedy had sought. Immediate priorities were bills to reduce taxes and guarantee civil rights. Using his skills of persuasion and calling on the legislators' respect for the slain president, in 1964 Johnson succeeded in gaining passage of the Civil Rights Bill. Introduced by Kennedy, it was the most far-reaching piece of civil rights legislation enacted since Reconstruction. Soon Johnson addressed other issues as well. By the spring of 1964, he had begun to use the name "Great Society" to describe his reform program, and that term received even more play after his landslide victory over conservative Republican Barry Goldwater in the presidential election of that year.

On the economic front, Johnson pushed successfully for a tax cut, then pressed for a poverty program Kennedy had initiated. "This administration today, here and now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America," he announced. The Office of Economic Opportunity provided training for the poor and established various community-action programs to give the poor themselves a voice in housing, health and education programs.

Medical care came next. Truman had proposed a centralized scheme more than 20 years earlier, but had failed to gain congressional passage. Under Johnson's leadership, Congress enacted Medicare, a health insurance program for the elderly, and Medicaid, a program providing health-care assistance for the poor.

Similarly, Johnson succeeded in the effort to provide aid for elementary and secondary schooling where Kennedy had failed. The measure that was enacted gave money to the states based on the number of their children from low-income families. Funds could be used to assist public- and private-school children alike.

The Great Society reached even further. A new housing act provided rent supplements for the poor and established a Department of Housing and Urban Development. An immigration measure finally replaced the discriminatory quotas set in 1924. Federal assistance went to artists and scholars to encourage their work.

The Johnson administration also addressed transportation safety issues, in part because of the efforts of a young lawyer, lobbyist and consultant named Ralph Nader. In his 1965 book, Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile, Nader argued that many cars could cause death or damage in even low-speed accidents. Nader said that automobile manufacturers were sacrificing safety features for style, and he named specific models in which faulty engineering contributed to highway fatalities. In September 1966, Johnson signed into law two transportation bills. The first provided funds to state and local governments for developing safety programs, while the other set up federal safety standards for cars and tires.

In all, the Great Society was the greatest burst of legislative activity since the New Deal. But support for the Johnson administration policies began to weaken as early as 1966. Some of Johnson's programs did not live up to expectations; many programs went underfunded. Still, the Great Society achieved some reductions in poverty -- between 1965 and 1968, for example, black-family income rose from 54 percent to 60 percent of white-family income.

<http://countrystudies.us/united-states/history-121.htm> (10/13/13)

John Gardner, Architect of the Great Society

When John Gardner became the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, he was joining President Lyndon Johnson not just as a cabinet member, but as the engineer of his ambitious agenda of social reform known as the "Great Society."

In the wake of President Kennedy's assassination in 1963, a wave of sympathy and public support enabled President Johnson to pass a number of Kennedy Administration proposals including the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Building on this momentum, Johnson introduced his own vision for America: "the Great Society" -- in which America ended poverty, promoted equality, improved education, rejuvenated cities, and protected the environment. This became the blueprint for the most far-reaching agenda of domestic legislation since the New Deal -- legislation that has had a profound effect on American society.

Perhaps driven by his own humble beginnings, Johnson declared a "War on Poverty" as central to building the Great Society. In 1960, despite the prosperity of the times, almost one-quarter of all American families were living below the poverty line, and entire regions of the country, like central Appalachia, were bypassed by the economic growth of the postwar years. Moreover, technological advances in industry were also changing job requirements for American workers. The good-paying, unskilled jobs of the past were disappearing, and those without education and skills were being left behind.

The first piece of Great Society legislation, the Economic Opportunity Act 1964, tried to give people tools to get out of poverty. The bill created a Job Corps similar to the New Deal Civilian Conservation Corps; a domestic peace corps; a system for vocational training; and Head Start, a pre-school program designed to prepare children for success in public school. The bill also funded community action programs and extended loans to small businessmen and farmers.

Johnson's landslide re-election victory over Republican opponent Barry Goldwater in 1964 added to the momentum of Great Society reforms. Over the next four years, Johnson enacted a flurry of legislation. One of the most ambitious efforts was the establishment of Medicare to provide health care for America's senior citizens.

In 1964, 44 percent of seniors had no health care coverage, and with the medical bills that come with older age, this propelled many seniors into poverty. In fact, more than one in three Americans over 65 were living below the poverty line -- more than double the rate of those under 65. Medicare was an important and big change in American health care -- it was called the "biggest management job since the invasion of Normandy" -- and it was up to John Gardner to make it work. He helped shepherd Medicare to reality, and the results have been extraordinary: virtually all seniors now have health care, and the poverty rate for the elderly has fallen to approximately one in ten -- a rate lower than that of the general population. Along with Medicare, the Johnson Administration established the Medicaid program to provide health care to the poor.

Education reform was also an important part of Johnson's Great Society, and a particular passion of Gardner's. In 1964, 8 million American adults had not finished 5 years in school; more than 20 million had not finished eight years; and almost a quarter of the nation's population, around 54 million people, hadn't finished high school. In 1965, Congress passed the groundbreaking Elementary and Secondary Education Act which for the first time provided federal funding for education below the college level passed the Higher Education Act, which created a National Teachers Corps and provided financial assistance to students wishing to attend college.

Urban renewal and conservation was the third major component of the Great Society. Ever since the end of World War II, cities faced a shortage of good, affordable housing, At the same time, the suburbanization of America along with the changing economy meant that many businesses began to leave city centers, an exodus that was accelerated by urban rioting that began in earnest after the Watts riot in 1965 in Los Angeles, and continued throughout Johnson's term. As part of a response, Johnson signed the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965 that established the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and expanded funding for public housing. In addition, he provided aid to cities to rebuild blighted areas.

Johnson's ambitions for a Great Society were checked by his ambitions in Vietnam. The cost of the war in Vietnam along with the costs of his domestic programs strained the economy. Moreover, as the war became more and more unpopular, Johnson lost the political capital needed to continue these reforms. Critics of the Great Society also charged that these programs just created bureaucracies and threw money at problems without producing results. Still others rejected the notion that the federal government should be undertaking these tasks at all. Nevertheless, the impact of the Great Society in many areas is undisputed as political leaders today still wrestle with how to deal with these issues of poverty, health care, and education.

<http://www.pbs.org/johngardner/chapters/4c.html> (10/13/13)

Thatcher-Reagan Reaction

Thatcher & Reagan in perspective

(Reagan's apology to Thatcher for the Invasion of Grenada, 1983)

(Reagan's apology to Thatcher for the Invasion of Grenada, 1983)

Thirty years ago Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher brought about a revolution in thinking and policy in both economics and foreign affairs. The economies of the United States and Britain are today fundamentally different because of what they did. The collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union is also the result of their policies. Of course, Reagan and Thatcher have always had their critics, some of whom now believe that the world economy will revert to pre-Reagan and pre-Thatcher policies. But anyone who recalls what the American and British economies were like before Reagan and Thatcher, and who knows the changes that they introduced, must also recognize that the world cannot go back.

Reagan and Thatcher were revolutionaries in their thinking and in their ability to inspire others to accept fundamental change. Reagan had four key economic goals when he assumed office in 1981: reduce inflation, reduce high personal tax rates, reduce the size of government, and reduce regulation of the private sector.

Inflation came down rapidly, from more than 10 percent in 1981 to less than 4 percent in 1983, because Reagan backed the tough monetary policies of US Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker. Today an inflation rate of close to zero is the accepted goal of US policy.

Reagan's tax policies reduced the top income-tax rate from 70 percent in 1980 to 28 percent in 1986. Although the top rate has climbed back to near 40 percent, no one proposes a return to pre-Reagan levels.

Although Reagan could not bring down spending on entitlement programs for retirees, America's non-defense discretionary spending was reduced by one-third, from 4.7 percent of GDP in the 1980 to 3.1 percent in 1988. It stood at 3.4 percent in 2008.

Finally, regulations were reduced in a wide range of industries, including air transport and the financial sector.

Fundamental problems

Reagan characterized the Soviet Union as an "evil empire" and increased defense spending to challenge Soviet aggression and capabilities. The collapse of the Soviet Union and of communism were, in part, dramatic responses to US policies and to the inability of the Soviet economy to keep up with the West. There will be no going back here as well.

When Margaret Thatcher became prime minister of Britain in 1979, she faced an economy with much more fundamental problems than those in the US. Britain was a much more socialized economy, with widespread government ownership and dominant trade unions. She privatized the major government-owned industries and sold government-owned housing to tenants. No one is proposing to re-nationalize industries or to take back that housing. Trade union power was permanently broken after long and painful national strikes.

The top tax rate on wage income was cut in half during her tenure as prime minister, falling from over 80 percent when she took office to 40 percent at the end of her tenure. Additional taxes on investment income meant the top tax rate before Thatcher came to power was initially above 95 percent. Although the top rate of income tax in Britain is currently at 45 percent, there is no thought of going back to pre-Thatcher taxes.

No going back

Faced with high inflation, Thatcher backed a monetarist approach that supported high interest rates and succeeded in sharply reducing inflation. Today Britain has an independent central bank with an inflation target of 2 percent. Thatcher supported Britain's entry into the European Union in order to benefit from free trade, but she forcefully opposed joining the single currency. The Labour government that followed her continued the policy of remaining outside the euro zone, as have the Conservatives under Prime Minister David Cameron. Indeed, the current - often heated - debate over the extent of Britain's future involvement in Europe and Cameron's demands to reform and water down the EU's influence on London, bears the hallmarks of the Thatcher years.

Financial deregulation made London a global financial center. Some of those regulatory changes may be reversed, but Britain is unlikely to jeopardize an important component of its economy by returning to pre-Thatcher financial rules.

Policies do evolve as conditions change and as we learn from experience. But the dramatic policy changes in the US and Britain under Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher brought about such profound improvements that there is no going back.

-- Martin Feldstein, a professor of economics at Harvard, was formerly Chairman of President Ronald Reagan's Council of Economic Advisors and President of the National Bureau for Economic Research.

<http://www.dw.de/the-reagan-thatcher-revolution/a-16732731> (10/13/13)

Stark differences between Thatcher & Reagan

Ronald Reagan attacked unions, deregulated like crazy, lowered taxes on rich people and ratcheted up the Cold War like nobody’s business. Thatcher did all of these things as well, but the difference was that there was a precedent for Reagan. Many of his policies were hinted at as early as the late ’60s and early ’70s when he was governor of California and even as far back as the late ’40s and early ’50s when he was an actor dealing with the Red Scare in Hollywood. Reagan may have changed America, but America was changing already and he just pushed that wave along. Thatcher, on the other hand, ushered in policies that were at once unpopular and worse far beyond the pale of what even most Tories thought was necessary at the time. Privatizing large swaths of British transportation, ripping apart the social safety net and increasing taxes on the poor were radical moves at the time in England. This is not to say that Thatcher wasn’t loved, and that she wasn’t able to get re-elected in 1983 and 1987 but if you were to compare the end results of her time in office to Reagan's the differences are quite stark.

When Reagan left office in 1988 the unemployment rate was down, Communism was destroyed, and his own party praised him until the day he died. Thatcher was kicked out of power by her own party in 1990, unemployment was better than we she took office but was still at unprecedented levels, and John Major managed to keep the Conservatives in power in part because he was NOT a pure Thatcherite.

Big Ideas, Essential Questions, and Higher Order Thinking

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 11:11 AM

- URL: https://slulibrary.saintleo.edu/democracy

- Print Page

(Reagan's apology to Thatcher for the Invasion of Grenada, 1983)

(Reagan's apology to Thatcher for the Invasion of Grenada, 1983)