LIBRARY

UE: POL 110-HA: Democracy in Troubled Times

- Course Introduction

- Is Democracy in Decline?

- Democracy in Ancient Athens

- Roman Republic

- American Revolution

- French Revolution

- Tocqueville - Democratic Defects

- Tocqueville - Democratic Remedies

- American Civil War

- Rise of Democracy in Great Britain

-

British Empire to Commonwealth

- The Takeaway - What You Need to Know

- Overview - From Empire to Commonwealth

- Commonwealth Democracies and Federalism

- Canada - America's Northern Neighbor

- Quebec Separatism

- Big Ideas, Essential Questions, and Higher Order Thinking

- VIDEO RESOURCES - British Empire

- OVERVIEW - irish Independence

- Michael Collins - Freedom Fighter

- Northern Ireland - The Troubles

- American Century <20th Century>

- Communism and Fascism in the 20th Century

- Presidential Democracy in France's 5th Republic

- Collective Security & World Organizations

- Mass Movements Abroad

- Contemporary Challenges to Western Democracy

- For Further Research

-

Spartan Republic

The Takeaway - What You Need to Know

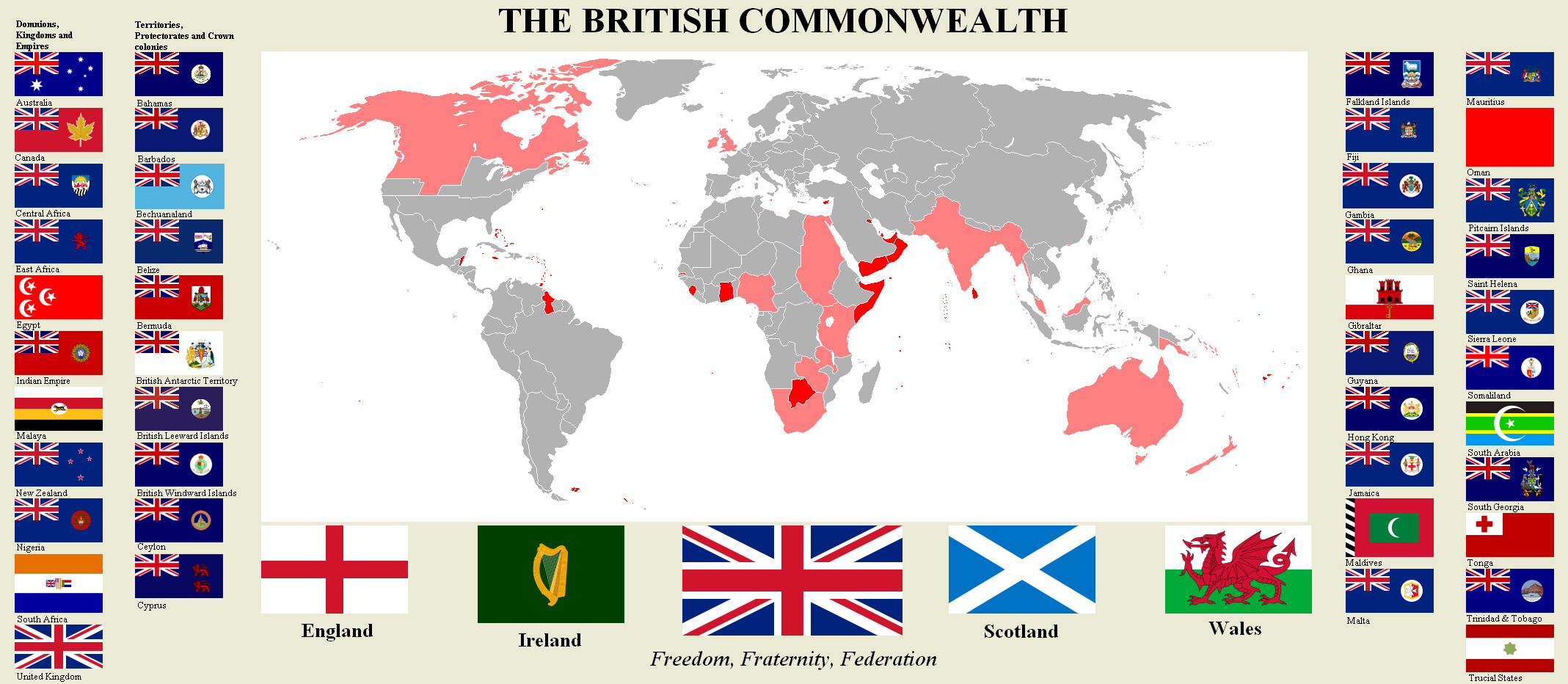

Overview - From Empire to Commonwealth

Since the late-1600s in Great Britain the political distinction between "Tories" (pro-Monarchist Conservatives) and the "Whigs" ( pro-Parliament Liberals) came to identify these competing rival forces as the first two modern parties in a "pure" bi-party democratic domestic political system.

However, within the Empire both parties agreed on supporting commercial and naval growth abroad with control of strategic bases dominating international trade, like Gibraltar, Malta, Singapore, Honk Kong; trade-post islands, like Jamaica, and rich colonies, like America, India, Australia, South Africa, Nigeria.

Only in the 1890s did the two parties develop rival attitudes also towards Imperial politics, with the Conservatives continuing the expansion of the British Empire as a symbol of international power and commercial preeminence under Prime Ministers Palmerston and Disraeli, while the Liberals under Prime Minister Gladstone increasingly resisted further expansions and came to look at the Empire as a source of oppression of the indigenous colonized people.

By the early-1900s, the growth of the rival Labour Party, with its Socialist and anti-colonialist base, made the quest for empire untenable. Already by 1900-06 the British government had given self-governing autonomy to the White Dominions, i.e., Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, excepting neighboring Ireland. The non-white colonies remained equally exploited and underprivileged, except for their ruling British settlers.

The convulsions of World War I led to the Irish Easter Revolt and subsequent granting of Dominion status to Ireland (a couple of years before its eventual secessionist independence) after centuries of oppression and irresolution.

By the 1935 Westminster Conference, the Empire officially became a Commonwealth with equal self-governing rights only for the White Dominions. But the next year the British Parliament, under pressure of Labour (which had grown to become the second-strongest party), the remaining Liberals, and most British public opinion, embraced Mahatma Gandhi's nationalist quest for equal rights and made British India the first non-White Dominion.

Finally World War II (1939-45) led to full independence for the White Dominions (1945) and reluctantly also for India (1948), despite Conservative opposition.

Consequently, by the 1950s all parties under Labour's leadership -- and Prime Minister Wilson's "Winds of Change" -- agreed to elevate many indigenous colonies to Dominion status, which included Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia, but the British politico-economic decline during the Cold War allowed for full independence of all colonies in the 1950s-65.

The Commonwealth thereafter rapidly transformed itself from empire to a weak international organization of independent nations commercially tied to Great Britain and ceremonially tied its Monarchy.

Copyright © 2013 - Marco Rimanelli, Ph.D. Saint Leo University

Commonwealth Democracies and Federalism

Decolonization and the Commonwealth

Since the late-1500s England and then Great Britain's United Kingdon aggressively promoted commercial and naval expansion abroad with control of strategic bases dominating international trade (like Gibraltar, Malta, Singapore, Honk Kong), trade-post islands (like Jamaica, Ceylon, Bahamas) and rich colonies (like America, India, Australia, South Africa, Nigeria). Only since the 1890s did the domestic British consensus towards Imperial politics broke apart, with the Conservative Party ("Tories") continuing the expansion of the British Empire as a symbol of international power and commercial preeminence under Prime Ministers Parlmerstone and Disraeli, while the Liberal Party (old "Whigs") under Prime Minister Gladstone increasingly resisted further expansions and came to look at the Empire as a source of oppression of the indigenous colonized people.

By the early-1900s the growth of the rival Labour Party with its Socialist and anti-colonialist base made the quest for empire untenable. Already by 1900-06 the British government had given self-governing autonomy to the White Dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa) compared to the other colonies that remained equally exploited and underprivileged except for their ruling British settlers. The politico-military and socio-economic convulsions of World War I led also to the Irish Easter Revolt and subsequent granting of Dominion status to Ireland (a couple of years before its eventual secessionist independence) after centuries of oppression and irresolution since 1840s over granting or not Irish "home rule".

By the 1931 Statute of Westminster the Empire officially became a Commonwealth with equal self-governing rights only for the White Dominions, but the next year the British Parliament under pressure of Labour (now the second-strongest party), Liberals and most British public opinion embraced Mahatma Gandhi's nationalist quest for equal rights and made British India the first non-White Dominion. Finally World War II (1939-45) led to full indepndence for the White Domnions (1945) and reluctantly also for India (1948), despite the Conservatives' opposition.

Consequently, by the 1950s all parties under Labour's leadership (Prime Minister Wilson's "Winds of Change") agreed to elevate many indigenous colonies to Dominion status (Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia), but the British politico-economic decline during the Cold War finally allowed full independence for all colonies in the 1950s-65 ("Decolonization"). Thus, the Commonwealth transformed itself from empire to a weak international organization of independent states ("Commonwealth of Nations") tied to Great Britain and its Monarchy, despite the increasingly symbolic and irrelevant nature of the Comonwealth since the 1990s.

A distinct feature of the Comonwealth is its accidental dual-level federalism: Since the early-1900s most White Dominions (which helped transform the British Empire into the British Commonwealth) were themeselves based on domestic federalism similar to the example of post-independence United States. Thus, Canada, Australia and South Africa emerged as federal Dominions organized in Provinces/States (while New Zealand refused to merge with Australia, and likewise Southern Rhodesia turned down merger with South Africa). Thereafter, as Commonwealth also many non-White Dominions became independent as new federal states: India, Pakistan, Malaysia, Nigeria, etc.

The Commonwealth as an organiztion comprises 53 independent ex-colonial states by the 2000s,from the

The main policy-making organ is the biannual Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM), addressing common security and Commonwealth Declarations on principles, like the Declaration of Commonwealth Principles on Democracy (Singapore 1971). The Commonwealth Finance Ministers meet annually, while a Commonwealth Secretariat Task-Force on Small States coordinates political, security, social, economic and environmental needs of its 32 smaller members, supporting the Commonwealth Ministerial Group on Small States (1993) and Commonwealth Consultative Group on Small States (1994). The Commonwealth fosters economic and political cooperation on a voluntary basis, and has strongly promoted United Nations (U.N.) sanctions against Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (1965-80, later renamed Zimbabwe), or isolating South Africa for its Apartheid racial segregation.

The Commonwealth’s key states are: Australia, Bangladesh, Brunei, Canada, Great Britain, India, Kenya, Malaysia, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan (suspended 1972-89, 1999-2001), Singapore, South Africa (suspended 1970s-93) and Zimbabwe (suspended 2001-current), plus 32 smaller members with populations below 1.5 millions, like Fiji (suspended 1987-97), Jamaica and Pacific islands. The Commonwealth acts on mediation, conflict-prevention, election-monitoring, economic development and since 1983 as an international pressure group for its lesser members through the Joint Office for Commonwealth Permanent Missions to the U.N. (1996), or lending legal help to New Zealand and South Pacific Forum members at the International Court of Justice since 1995 against France’s Pacific nuclear tests.

Copyright © 2013 - Marco Rimanelli, Ph.D. Saint Leo University

Canada - America's Northern Neighbor

The Origin of Canadian Federalism

Canada in 1867

Source: Library and

Archives Canada

The Province of Canada had been established in 1841 following the Act of Union which amalgamated two hitherto separate colonies, Lower Canada (majority Francophone) and Upper Canada (Anglophone), which had their own elected legislative assemblies that enabled them to make certain respective domestic political choices.

After the union of 1841, it proved virtually impossible for a single government to ensure political stability, despite measures designed to preserve the specificity of each of the communities.

An initial meeting to discuss the reorganization of independent Canada was held in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, in September 1864. A proposal for a maritime union of the Atlantic coast colonies quickly gave way to the proposal for a federal union of all the colonies advocated by the delegates from the Province of Canada.

The maritime colonies expressed interest in the proposals by the Province of Canada, which were to their advantage as well. Although similar with respect to language, they were different from both an historical and socio-economic standpoint; through their own elected legislative assemblies, they already exercised a certain level of autonomy over domestic policy.

A second meeting was held in Quebec City, Province of Canada, in October 1864 , at which the division of powers between the constituent entities and a federal government was discussed, among other things. The 72 Resolutions of Quebec included proposals that the existing legislative assemblies (or re-established, in the case of the Province of Canada) would exercise responsibilities related to local issues and that a new federal Parliament would assume powers related to common policies, including in the economic and military fields.

The foundations were laid for Confederation in 1867. Canada would originally be composed of four constituent entities: the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec, the latter resulting from the division of the Province of Canada. Over the years, the other British North American colonies and all territories in British North America would also become part of Canada, as either provinces or territories.

The new federation was born in large part out of the need to reflect two different linguistic realities. At the time of the first census after Confederation, Canadians of French origin accounted for 31.1% of the population. The vast majority of them, or 85.5%, lived in the new province of Quebec, while some 150,000 others lived in the other provinces.

The men who would become known as the Fathers of Confederation oversaw the creation of a federation which protected the rights of Quebec's Francophone population - which was determined to preserve its language, its religion and its law - and allowed for the use of both French and English in the federal Parliament, the Legislative Assembly of Quebec, and the federal courts. That protection and recognition of the French language and culture have greatly evolved since 1867.

http://www.pco-bcp.gc.ca/aia/index.asp?lang=eng&page=federal&sub=why-pourquoi&doc=why-pourquoi-eng.htm (09/29/13)

Canadian and U.S. Constitution Set Side-by-Side

The centralist nature of Canadian federalism is easily demonstrated when one compares it with the original federal constitution of the United States. It is to be remembered that it was an obvious design of the Fathers of Confederation to reverse the process at work in the United States (States Rights) and to empower the central government of Canada with all of the powers necessarily incidental to national sovereignty. It appeared to the Fathers of Confederation that it was the weakness of the "center" which was the major defect of the American constitution and they determined that we needed to strengthen ours to avoid the difficulties (civil war) in which the Americans were found at the time when Canadian federalism was being drafted.

Following the Charlottetown Conference, Macdonald made the following comments at a banquet in Halifax (September 12, 1864) where he explained his views regarding the American constitution:

It has been said that the United States Government is a failure. I don't go so far. 0n the contrary I consider it a marvelous exhibition of human wisdom. It was as perfect as human wisdom could make it, and under it the American States greatly prospered until very recently; but being the work of men it had its defects, and it is for us to take advantage by experience, and endeavor to see if we cannot arrive by careful study at such a plan as will avoid the mistakes of our neighbors. In the first place we know that every individual state was an individual sovereignty - that each had its own army and navy and political organization - and when they formed themselves into a confederation they only gave the central authority certain specific rights appertaining to sovereign powers. The dangers that have risen from this system we will avoid if we can agree upon forming a strong central government - a great Central Legislature - a constitution for a Union which will have all the rights of sovereignty except those that are given to the local governments. Then we shall have taken a great step in advance of the American Republic

Macdonald was true to his words as can be shown by the following comparison.

by Claude Bélanger

<http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/federal/compare.htm> (09/29/13)

TEXT: Federalism in Canada - Basic Framework and Operation

Canadian Federalism seen as a Positive Influence

A theme of the new Canadian political history is that Canada’s Confederation in 1867 is best understood not as an act of national unification, which is how many English-Canadian historians have seen it for decades, but rather as a compact between two autonomous nations, which is of course what French-Canadian historians have maintained all along.

This is the argument of Paul Romney, in a recent book called Getting It Wrong: How Canadians Forgot Their Past and Imperiled Confederation. Alas, Romney’s title indulges in a common Canadian practice of whipping up fears about the future in order to sell books about the past. But his argument is compelling and potentially transformative. Romney and others like him are recovering a lost tradition in English-Canadian politics and political history, one that is far more compatible with French-Canadian historiography, and with the realities of Canadian federalism, than the centralist mythology constructed by English Canadian historians since the 1930s.

Both English and French Canadians, Romney argues, embraced federalism in 1867 not to forge a centralized nation-state called Canada but to establish a true federation of autonomous provinces. For a substantial constituency of Upper and Lower Canadians, the real intent of Confederation was to undo the hated Union Act of 1841, when the British responded to the rebellions of 1837 by forcing Upper and Lower Canada into one administrative unit. When nineteenth-century Canadians campaigned for “responsible government,” Romney demonstrates, most meant provincial government. So the Dominion of Canada was a decentralized federation by design.

Why is this conclusion interesting from a transnational point of view? For one thing, it offers a basis for much-needed dialogue between French and English Canadians and their historians. As Romney points out, Quebecois nationalism and English-Canadian nationalism now rest on mutually incompatible histories of Confederation. But this was not always so; the designs of 1867 accommodated English- and French-Canadian aspirations without contradiction.

More broadly, a political history of Canadian federalism that accepts the legitimacy of provincial autonomy can stop denying or lamenting what is one of the most interesting things about Canada from an international point of view: the persistent importance of regions and regionalism to Canada’s collective political experience. Unlike the United States and many other developed Western countries, and contrary to conventional wisdom in the mid-twentieth century, the modernization and industrialization of Canada did not lead to political centralization or to the economic or social homogenization of provinces and regions. Western Canada, Atlantic Canada, Northern Canada, Ontario, and Quebec remain profoundly and fundamentally distinct. Economic development is highly uneven and regional differences are powerful and real.

Yet this heterogeneity does not mean that Canadian federalism has failed or is falling apart. Outsiders are often impressed by the achievements of Canadian federalism and bemused by Canadians’ sense of perennial crisis. Canadian federalism is only “failing” if the sole definition of success is a monolithic national identity coterminous with the borders of a centralized state. “For more than a quarter-century, the federation has been wracked by crisis and by worried scholarly commentary,” observe Robert Wardhaugh and Barry Ferguson. They do not themselves share in the panic. Somehow, they point out, the federation abides. Though not without its shortcomings, Canada has been remarkably successful in managing diversity and heterogeneity. A history written to respect and explain those successes would be more useful and accessible to non-Canadian audiences than our traditional narrative of English-Canadian nation-building and its failures.

by Robert McDougall

<http://nuevomundo.revues.org/59404> (09/29/13)

Quebec Separatism

(Courtesy of The Huffington Post)

(Courtesy of The Huffington Post)

Quebec Separatism

The current debate about Quebecois separatism is the culmination of centuries of tension between English-Canada and French-Canada. Quebec was originally discovered and colonized by the French, but surrendered to the English following the French and Indian Wars and Treaty of Paris of 1763. The English were actually rather magnanimous in their treatment of the Quebecois (in stark contrast with the brutal deportation of the Acadians from Nova Scotia). The Quebecois were allowed to keep their religion and language, but could not hold public office unless they converted to Protestantism, which for the Catholic Quebecois was out of the question. As more English-Canadians (Anglophones) began to move into Quebec with the onset of industrialization, Quebec found itself with an Anglophone minority largely controlling a linguistically, culturally, and religiously distinct majority. As the Quebecois had always resented the English conquest of Quebec, this situation was bound to cause resentment and tension between the two groups.

With the 1867 founding of the Dominion of Canada, French was given status as official language in the federal government and in the provincial government in Quebec. Despite this, in 1870 New Brunswick, with its substantial Acadian minority in the Saint John Valley, abolished all Catholic schools, and later Manitoba banned French schools. This led to violence in Quebec as they became more focused on the plight of French-Canadians outside of Quebec. This sentiment is epitomized by Quebec's refusal to send troops to support Great Britain during World War I until they "got their schools back."

Quebec society was undergoing considerable changes in the 20th century, moving away from its agrarian, Catholic, and conservative past and becoming increasingly urban and middle class. Premier Maurice Duplessis of the Union Nationale, a Quebecois nationalist and economic conservative, tried to keep Quebec agrarian and conservative, but the pressures to reform were too much. In the 1960s the movement to defend Quebecois culture and language moved into the political arena with Liberal Premier Jean Lesage's "Quiet Revolution," which included reforms to the social and educational infrastructure, controls on corruption, nationalization of power companies, and limiting the Catholic church's influence on politics, all designed to modernize Quebec society. But with the Union Nationale's return to power in 1966 certain cleavages in Quebec's politics could be seen between the federalist Liberals who thought that any reforms could be completed within the current federal system, while the Union Nationale, though federalist, was a firm believer in gaining more provincial power for Quebec (the slogan of Union Nationale Premier Daniel Johnson was "Equality or independence". From the left fringes of this cleavage a movement began to emerge that thought that Quebec would never be able to realize its goals within the federalist system, or within Canada, and began to push for independence from Canada. As a result, the separatist Parti Quebecois was formed, led by Rene Levesque, a former Liberal. It was also around this time, at the 1967 Worlds Fair in Montreal, that French President Charles de Gaulle closed a speech with "Vivre le Quebec libre!" ("Long live free Quebec"), drawing anger from the Canadian government and the adoration of separatists. It was then that the modern separatist movement began in earnest.

This was also when the Front de Liberation Quebecois (Quebec Liberation Front, or FLQ) began its campaign of bombings across the province. They were inspired by Marxist ideology, especially by the Cuban Revolution, and sporadically planted bombs, including at the Montreal Stock Exchange, beginning in 1963. The FLQ's campaign came to a head in 1970 with the kidnappings of British trade commissioner James Cross and Pierre Laporte, Quebec's Minister of Labor. The kidnappings prompted Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to declare martial law in Montreal and suspend some civil liberties. Although the crisis ended with Laporte's murder (Cross was released unharmed), Canadians, both French and English, approved of Trudeau's actions and viewed the FLQ as a rogue band of extremists, which they were.

The Parti Quebecois became the Official Opposition to Premier Henri Bourassa's Liberal government in 1973 and finally took power in 1976. The Parti Quebecois instantly introduced measures to strengthen and protect the use of the French language in the province, making it the official language of government and the courts, as well as the language of business (all shop signs in Quebec must have French twice as large and twice as prominent than English). Most infamous was the passage of Bill 101, which in addition to restricting English-language education, it required that all immigrants moving to Quebec enroll in French-language schools, regardless of the language they previously spoke. The charter also changed English place-names and imposed French as the language of business, court judgments, laws, government regulations, and public institutions. Finally, the Parti Quebecois called a referendum in the province on the question of separation from Canada in 1980, but it was defeated with only 40% voting in favor.

<http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/quebec.htm> (10/01/13)

In 1987 the Meech Lake constitutional accord recognized Quebec as a "distinct society" and transferred extensive new powers to all the provinces. Quebec promised that it would accept the 1982 constitution if the accord was approved by all the rest of the provinces. The House of Commons ratified the Meech Lake accord on June 22, 1988, but the accord died on June 23, 1990, after Newfoundland and Manitoba withheld their support. A new set of constitutional proposals hammered out by a parliamentary committee was agreed upon in 1992. They called for decentralization of federal powers, an elected Senate, and special recognition of Quebec as a distinct society. In a referendum held in October 1992, Canadians decisively turned down the constitutional changes. Quebec voters narrowly rejected secession from Canada in a 1995 referendum.

<http://www.linksnorth.com/canada-history/quebecsep.html> (10/01/13)

TEXT: What does Quebec separatism look like in 2013 - An Interview with Jean-Claude Sylvain Guay

Big Ideas, Essential Questions, and Higher Order Thinking

Class Debate

- Was British colonialism a thoroughly bad thing for the colonized people?

- Is Canadian socialism better than American capitalism?

- Should Pakistan have been allowed to secede from India?

VIDEO RESOURCES - British Empire

-

The Day the Troubles Began 1/2 [10:10]

OVERVIEW - irish Independence

The 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rebellion, was an armed uprising of Irish nationalists against the rule of Great Britain in Ireland. The uprising occurred on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, and centred mainly in Dublin. The chief objectives were the attainment of political freedom and the establishment of an Irish republic. Centuries of discontent, marked by numerous rebellions, preceded the uprising. The new crisis began to develop in September 1914, following the outbreak of World War I, when the British government suspended the recently enacted Home Rule Bill, which guaranteed a measure of political autonomy to Ireland. Suspension of the bill stimulated the growth of the Citizen Army, an illegal force of Dublin citizens organised by the labour leader Jim Larkin (died 1948) and the socialist James Connolly (1870-1916); of the Irish Volunteers, a national defence body; and of the extremist Sinn Fein. The uprising was planned by leaders of these organisations, among whom were the British consular agent Sir Roger David Casement, the educator Padhraic Pearse (1879-1916), and the poet Thomas MacDonagh (1878-1916).

Hostilities began about noon on April 24, when about 2000 men led by Pearse seized control of the Dublin post office and other strategic points within the city. Shortly after these initial successes, the leaders of the rebellion proclaimed the Independence of Ireland and announced the establishment of a provisional government of the Irish Republic. Additional positions were occupied by the rebels during the night, and by the morning of April 25 they controlled a considerable part of Dublin. The counteroffensive by British forces began on Tuesday with the arrival of reinforcements. Martial law was proclaimed throughout Ireland. Bitter street fighting developed in Dublin, during which the strengthened British forces steadily dislodged the Irish from their positions. By the morning of April 29, the post office building, site of the rebel headquarters, was under violent attack. Recognising the futility of further resistance, Pearse surrendered unconditionally in the afternoon of April 29.

The inside of the General Post Office after the surrender

The British immediately brought the leaders of the uprising to trial before a field court-martial. Fifteen of the group, including Pearse, Connolly, and MacDonagh, were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad. Four others, including the American-born Eamon de Valera, received death sentences that were later commuted to life imprisonment, although de Valera and some others were granted amnesty the next year. Casement was convicted of treason and hanged. Many others prominently connected with the rebellion were sentenced to long prison terms. The uprising was the first of a series of events that culminated in the establishment of the Irish Free State (predecessor of the Republic of Ireland) in 1921. Casualties were about 440 British troops and an estimated 75 Irish (below are their names). Property damage included the destruction of about 200 buildings in Dublin.

Michael Collins - Freedom Fighter

Michael Collins - Irish Freedom Fighter?

|

When he was 15, Michael Collins emigrated to London from County Cork. He worked as a clerk for the Post Office and he lived within the large Irish community in London. While in London, Collins joined Sinn Fein and the Gaelic League and in 1909, he became a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

|

Collins was sent to Richmond Barracks and then to Frongoch internment camp in Wales. He was released in December 1916 and immediately went back to Ireland. His goal now was to revitalise the campaign to get independence for Ireland. Collins was elected to the executive committee of Sinn Fein and he led a violent campaign against anything that represented British authority in Ireland - primarily the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Army. The murder of RIC officers brought a tit-for-tat policy from the British. Ireland, post-World War One, was a dangerous country to be in. The more killings that were carried out by Collins and the men he led in the newly formed Irish Republican Army (IRA), the more the British responded with like.

The notorious Black and Tans and the 'Auxies' were used by the British Army to spread fear throughout Ireland (though primarily in the south and west). Violence led to more violence on both sides. On November 21st, 1920, the IRA killed 14 British officers in the Secret Service. In reprisal, the British Army sent armoured vehicles onto the pitch at Croke Park where people were watching a football match, and opened fire on them. Twelve people were killed. In May 1921, the IRA set fire to the Custom House in Dublin - one of the symbols of Britain's authority in Ireland. However, many of those in the Dublin IRA were captured as a result of this action. The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, was given some blunt advice by his military commanders in Ireland. "Go all out or get out" - meaning that the army should be allowed to do as it wished to resolve the problem, or if this was not acceptable at a political level, the British should pull out of Ireland as the army was in an un-winnable position as matters stood then.

Eamonn de Valera, considered to be the leading republican politician in Ireland, sent Collins to London in October 1921 to negotiate a treaty. It was generally recognised by both sides that the situation as it stood in Ireland could not be allowed to continue. The difficult negotiations took three months before the treaty was signed by Collins and Arthur Griffiths. In December 1921, it was agreed that Ireland should have dominion status within the British Empire; i.e. that Ireland could govern itself but remain within the British Empire. The six northern counties were allowed to contract out of the treaty and remain part of the United Kingdom. To Collins, the treaty was simply the start of a process that, in his eyes, would lead to full independence for what was now the Irish Free State.

Collins is said to have commented when he signed the treaty that:

|

"I tell you, I have signed my death warrant" |

There were many in the south who believed that Collins had betrayed the republican movement. These people, including de Valera, wanted an independent and united Ireland. Some believed that Collins had sold out to the British government. Few seemed to realise that Collins was not a politician and that he had been put into a situation in which he had no experience of what to do. He was up against British politicians who were experienced in delicate negotiations. Some have argued that de Valera deliberately put Collins in this situation knowing that if he came back with an unacceptable treaty, it would seriously damage the reputation of Collins and weaken whatever political kudos he had in Ireland - therefore removing any potential threat he may have been to de Valera at a political level. It is known that Collins did not feel that he had the necessary knowledge and experience to get what was wanted and he asked de Valera to send others instead of him. Some, such as Countess Markievicz, openly called Collins a traitor to the cause.

The Dáil accepted the treaty by just seven votes. This, in itself, seemed a justification of what Collins had set out to achieve. Arthur Griffiths replaced De Valera as president of the Dáil and Collins was appointed chairman of the provisional government which would take over Ireland once the British had left. Those who did not support the treaty fell back on violence and a civil war took place in Ireland from April 1922 to May 1923. The IRA split into the 'Regulars' (those who supported the treaty) and the 'Irregulars' (those who did not).

On August 22nd, 1922, Collins journeyed to County Cork. He was due to meet troops of the new Irish Army. His car was ambushed at a place called Beal na mBlath and Collins was shot dead. To this day, no-one is completely sure what happened or who killed him. No-one else was killed in the ambush. Collins' body lay in state in Dublin for three days and thousands paid their respects. Thousands also lined the streets for his funeral procession.

History Learning Site

<http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/michael_collins.htm> (10/01/13)

See a Good Movie

|

Michael Collins Liam Neeson stars as the title character in this biopic about the Irish folk hero who led the fight against British rule some 80 years ago. Initially Collins’ role in the IRA was as "minister for Gun Running, Daylight Robbery, and Bloody Mayhem," but he eventually wearied of the bloodshed and negotiated a settlement. The compromise resulted in the establishment of the Irish Free State, but left Northern Ireland under the British. The film's interpretation of Irish history is intriguing, and the movie doesn't shy away from presenting controversies that still resonate today. |

Northern Ireland - The Troubles

The Troubles in Northern Ireland

The conflict in Northern Ireland during the late 20th century is known as the Troubles. Over 3,600 people were killed and thousands more injured. Over the course of three decades, violence on the streets of Northern Ireland was commonplace and spilled over into mainland Britain, the Republic of Ireland and as far afield as Gibraltar. Several attempts to find a political solution failed until the Good Friday Agreement, which restored self-government to Northern Ireland and brought an end to the Troubles.

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 11:11 AM

- URL: https://slulibrary.saintleo.edu/democracy

- Print Page