LIBRARY

UE: POL 110-HA: Democracy in Troubled Times

- Course Introduction

- Is Democracy in Decline?

- Democracy in Ancient Athens

- The Takeaway - What You Need to Know

- OVERVIEW - Ancient Athens

- Athenian versus American Democracy

- The Creation of Athenian Democracy

- Life of Pericles

- Liberal Arts and Sciences in Athens

- Pericles' Funeral Oration

- The Athenian Empire - The First Naval Empire

- The Trial & Death of Socrates

- VIDEO RESOURCES - Ancient Athens

- ONLINE TEXTS - Ancient Athens

- Recommended Reading

- Roman Republic

- American Revolution

- French Revolution

- Tocqueville - Democratic Defects

- Tocqueville - Democratic Remedies

- American Civil War

- Rise of Democracy in Great Britain

- British Empire to Commonwealth

- American Century <20th Century>

- Communism and Fascism in the 20th Century

- Presidential Democracy in France's 5th Republic

- Collective Security & World Organizations

- Mass Movements Abroad

- Contemporary Challenges to Western Democracy

- For Further Research

- Spartan Republic

The Takeaway - What You Need to Know

Ancient Athens is widely credited with creating the first true democracy. Its political institutions and practices admittedly are far removed from the way current democracies operate, but its ideals have inspired advocates of democracy for over twenty-five hundred years. Republican Rome has also served as standard by which to judge modern democracy, although it was less a democracy and more a mixed form of government, combining a traditional landed aristocracy with an urban-based democracy. The Framers of the U.S. Constitution were well acquainted with the history and failure of the Roman Republic and drew significant lessons from the ancient Romans.

OVERVIEW - Ancient Athens

Democracy as a form of government was born in Greece towards the end of the Sixth Century, B.C. It reached its fullest expression in ancient Athens where after an initial flourishing it followed an unsteady course for two hundred years, until Macedonian imperialism under Alexander the Great in 322, B.C., extinguished it.

Classical Athenian democracy is known to us through four primary sources: Thucydides' investigation of Athens's loss to Sparta in the Second Peloponnesian War, Plato's disparagement of the democratic life-style in Book VIII of the Republic, Aristotle's judicious weighing of democracy as one of the varieties of regimes in his Politics, and a ramshackle history of the evolution of Athenian political institutions, known as the Constitution of Athens, also attributed to Aristotle.

For over two thousand years, orators, historians, and philosophers who favored self-government looked to classical Athens for guidance and inspiration, and have adapted its democratic ideology to suit their purposes. Modern scholars, on the other hand, tend to reject the study of classical Athenian democracy as relevant to our times because of its extreme participatory nature, its bellicosity, its countenance of slavery, and its oppressive treatment of women.

Copyright © 2013 - Hudson Reynolds, Ph.D.

Athenian versus American Democracy

Ancient Democracy versus Modern Democracy

What we call democracies in the western world, especially in the United States, would be seen as something less by the ancient Athenians. They would assert that there is very little democracy here because Americans are not able to participate directly in their government.

The first Athenian democracy was created by Cleisthenes in 507 B.C, when the people elected him along with others who were dedicated to replacing the aristocratic oligarchy. This political change was accomplished through legislation, not violence.

The Athenian political system, before the reforms, had many elements of a democratic system, but was heavily influenced by the aristocratic class. The principle legislative body was the Assembly (Ecclesia) which consisted of all citizens who came to the assembly meetings. Because of the unwieldy character of so large a group, a council of 500 was created to debate and consider new legislation before it was brought before the assembly. Governmental administration was handled by ten senior magistrates, called Archons, who were elected by the people. When an Archon’s term of office ended he could become a member of the Areopagas, an aristocratic council of elders who acted as a court of appeal. Lastly, there was an elected board of ten generals who were in charge of commanding the army and navy during time of war. Aristocratic influence was seen in the Council of 500 which was heavily tilted toward the upper class. Archons, themselves, were wealthy aristocrats, and the Areopagas was made up of former Archons.

The new laws sought to break the aristocratic hold on high office by removing their influence. Candidates for Archon were now chosen by lot from the Council of 500. A system of ostracism was introduced to prevent accumulation of power. Any senior official deemed to be corrupt could be banished for ten years by a vote of the Assembly. Other changes included limiting the power of the Areopagas to appeal for murder trials, and transferring supervision of the conduct of government to the Council of 500.

This great Athenian democracy thrived through the time of Pericles 462-429 B.C, but was degraded during the Peloponnesian War, which ended in 404. The Athenians were defeated by Sparta and would never again experience the great democracy they had invented.

If we agree that the definition of democracy is anything we want it to be, then I suppose America has a democracy, but it’s funny how the term has be used by feminist types to suggest the Greeks didn’t have a democracy because women couldn’t vote. In their view, only contemporary America would meet the true definition. How absurd! Democracies are defined by the ability of people to have a say in government, not whether one class or the other has equal rights.

A political system will only be strong if informed citizens vote. That is citizens who are intelligent enough and motivated enough to analyze the issues before voting. Those who vote without knowledge of the issues or support candidates because they are told who to support are corrupt. Quality government comes from quality votes, not the number of them.

The other problem we have in the United States is that the people’s power ends with their vote. Because they elect representatives and do not participate in government themselves, their surrogates are open to the kind of corruption that makes them beholden to the rich and powerful rather than the people they represent.

-- posted by Mike Anderson

<http://mikeandersonpol.blogspot.com/2011/03/democracy-in-america-not-according-to.html> (09/18/13)

The Creation of Athenian Democracy

Solon's Social Reforms [594 BC]

In the 7th century B.C., economic crises coupled with the start of the age of tyranny elsewhere in Greece -- beginning in c. 650 with Cypselus of Corinth, led to unrest in Athens. In the final quarter of the century, the Draconian law code was so severe that the word 'draconian' was named after the man who wrote the laws. At the start of the next century, in 594 B.C., Solon, a widely traveled aristocrat and poet, was appointed sole archon to avert catastrophe in Athens.

While Solon enacted compromises and democratic reforms, he kept the social organization of Attica [see map of Greece] and the Athenians, the clans and tribes. Following the end of his archonship, political factions and conflict developed. One side, the men of the Coast (consisting mainly of the middle classes and peasants), favored his reforms. The other side, the men of the Plain (consisting mainly of Eupatrids 'nobles'), favored restoration of an aristocratic government.

Tyranny of Pisistratus [546 BC]

Pisistratus (6th C. - 528/7 B.C.*) took advantage of the unrest. He wrested control of the Acropolis in Athens by means of a coup in 561/0, but the major clans soon deposed him. That was only his first attempt. Backed by a foreign army and the new Hill party (composed of men not included in either the Plain or Coast parties), Pisistratus took control of Attica as constitutional tyrant (c. 546).

Pisistratus encouraged cultural and religious activities. He improved the Great Panathenaia, which had been reorganized in 566/5, adding athletic contests to the festival in honor of the city's patron goddess Athena. He built a statue to Athena on the Acropolis and minted the first silver Athena owl coins [see symbols of Athena]. Pisistratus publicly identified himself with Heracles and especially with the help Heracles received from Athena.

Pisistratus is credited with bringing rural festivals honoring the god of revelry, Dionysus, into the city, thereby creating the extremely popular Great Dionysia or the City Dionysia, the festival known for the great dramatic competitions. Pisistratus included tragedy (then a new literary form) in the festival, along with a new theater, as well as the theatrical competitions. He gave a prize to the 1st writer of tragedies, Thespis (c. 534 B.C.).

Anacreon of Teos and Simonides of Ceos sang for him. Trade flourished.

While first generation tyrants were generally benign, their successors tended to be more like what we envision tyrants to be [Terry Buckley]. Pisistratus' sons, Hipparchus and Hippias, followed their father to power, although there is debate as to who and how the succession was ordered:

"Pisistratus died at an advanced age in possession of the tyranny, and then, not, as is the common opinion, Hipparchus, but Hippias (who was the eldest of his sons) succeeded to his power."

Thucydides Book VI Jowett translation

Hipparchus favored the cult of Hermes, a god associated with small tradesmen, placing Herms along the roads. This is a significant detail because Thucydides uses it as a point of comparison between leaders in connection with the mutilation of the herms attributed to Alcibiades at the time of the Peloponnesian War [see Internet History Sourcebook].

"They did not investigate the character of the informers, but in their suspicious mood listened to all manner of statements, and seized and imprisoned some of the most respectable citizens on the evidence of wretches; they thought it better to sift the matter and discover the truth; and they would not allow even a man of good character, against whom an accusation was brought, to escape without a thorough investigation, merely because the informer was a rogue. For the people, who had heard by tradition that the tyranny of Pisistratus and his sons ended in great oppression...."

Thucydides Book VI Jowett translation

Hipparchus may have lusted after Harmodius...

"Now the attempt of Aristogiton and Harmodius arose out of a love affair....

Harmodius was in the flower of youth, and Aristogiton, a citizen of the middle class, became his lover. Hipparchus made an attempt to gain the affections of Harmodius, but he would not listen to him, and told Aristogiton. The latter was naturally tormented at the idea, and fearing that Hipparchus who was powerful would resort to violence, at once formed such a plot as a man in his station might for the overthrow of the tyranny. Meanwhile Hipparchus made another attempt; he had no better success, and thereupon he determined, not indeed to take any violent step, but to insult Harmodius in some secret place, so that his motive could not be suspected.

Ibid.

... but the passion was not returned, so he humiliated Harmodius. Harmodius and his friend Aristogiton, the men who are renowned for freeing Athens of its tyrants, then assassinated Hipparchus. They weren't alone in defending Athens against tyrants. In Herodotus, Volume 3 William Beloe says Hippias tried to get a courtesan named Leaena to reveal the name of Hipparchus' accomplices, but she bit off her own tongue so as not to answer. Hippias' own rule was considered despotic and he was exiled in 511/510.

See "Politics and Folktale in the Classical World," by James S. Ruebel. Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 50, No. 1 (1991), pp. 5-33.

The exiled Alcmaeonids wanted to return to Athens, but couldn't, so long as the Pisistratids were in power. By taking advantage of Hippias' growing unpopularity, and by gaining the support of the Delphic oracle, the Alcmaeonids forced the Pisistratids to leave Attica.

Cleisthenes' Democratic Revolution

Back in Athens, the Eupatrid Alcmaeonids, led by Cleisthenes (c. 570 - c. 508 B.C.), allied with the mostly non-aristocratic Coast party. The Plain and Hill parties favored Cleisthenes' rival, Isagoras, from another Eupatrid family. Isagoras appeared to have the numbers and the upper hand, until Cleisthenes promised citizenship to those men who had been excluded from it.

The 10 Tribes of Athens

Cleisthenes won the bid for power. When he became chief magistrate, he had to face the problems Solon had created 50 years earlier through his compromising democratic reforms -- foremost among which was the allegiance of citizens to their clans. In order to break such clan loyalties, Cleisthenes divided the 140-200 demes (natural divisions of Attica) into 3 regions: city, coast, and inland. In each of the 3 regions, the demes were divided into 10 groups called trittyes. Each trittys was called by the name of its chief deme. He then disposed of the 4 birth-based tribes and created 10 new ones composed of one trittys from each of the 3 regions. The 10 new tribes were named after local heroes:

- Erechthesis

- Aegeis

- Pandianis

- Leontis

- Acamantis

- Oeneis

- Cecropis

- Hippothontis

- Aeantis

- Antiochis.

The Boule (Council of 500)

The Areopagus and archons continued, but Cleisthenes modified Solon's Council of 400 based on the 4 tribes. Cleisthenes changed it to a Council of 500 to which

- Each tribe contributed 50 members.

- Each deme contributed a number proportional to its size. Over time, each member came to be, ??? instead of having the unwieldy 500 sitting day after day for the year of their office, each tribe sat on the administrative and executive council for 1/10 of the year.

- Chosen by lot

- From those citizens who were at least 30-years old, and then

- Approved by the outgoing council.

These groups of 50 men were called prytanies. The Council could not declare war. Declaring war and vetoing recommendations of the Council were responsibilities of the Assembly of all citizens.

Quiz on the Greek and Roman Tribes

Cleisthenes and the Military

Cleisthenes reformed the military, as well. Each tribe was required to supply a hoplite regiment and a squadron of horsemen. A general from each tribe commanded these soldiers.

Ostracism

Information on the reforms of Cleisthenes is available through Herodotus (Books 5 and 6) and Aristotle (Athenian Constitution and Politics). The latter claims that Cleisthenes was also responsible for the institution of ostracism, which allowed the citizens to get rid of a fellow citizen whom they feared was getting too powerful, temporarily. The word ostracism comes from ostraka, the word for the potsherds on which the citizens wrote the name of their candidates for the 10-year exile.

More on Ostracism

Sources

- J.B. Bury: A History of Greece

- (pages.ancientsites.com/~Epistate_Philemon/newspaper/cleis.html)

- (http://www.pbs.org/empires/thegreeks/characters/cleisthenes_p8.html)

- (www.pagesz.net/~stevek/ancient/lecture6b.html) The Athenian Origins of Direct Democracy

- (www.alamut.com/subj/artiface/deadMedia/agoraMuseum.html) Technology of Ancient Democracy

- Aspects of Greek History 750-323 BC: A Source-Based Approach, by Terry Buckley (2010)

- "The Career of Peisistratos Son of Hippias," by Michael F. Arnush; Hesperia Vol. 64, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1995), pp. 135-162.

-- copied from About.com 9/9/13

Product of N.S. Gill, a Latinist and freelance writer with a longtime focus on the classical world

Life of Pericles

Who was Pericles?

Pericles was a leader of Athens who was responsible for rebuilding Athens following the Persian Wars. He was also leader of Athens during the Peloponnesian War, but he died of the plague that ravaged the city. He was so important that the era in which he lived (during the 5th Century B.C.) is known as the Age of Pericles.

Family of origin

Pericles was the son of Xanthippus and Agariste. Xanthippus, a military leader in the Persian Wars, victorious at the battle at Mycale, was the son of one Ariphron and the father of another. Ariphron II was a candidate for ostracism. Xanthippus himself was ostracized in spring 484. Agariste was from the Alcmeon family, which was accused of treachery at the Battle of Marathon.

1st Public Office

Pericles, Cimon, and Democracy

In the 460s, the Helots rebelled against the Spartans who asked for help from Athens. In response to Sparta's request for help, Athens' leader, Cimon, led troops into Sparta. The Spartans sent them back, probably fearing the effects of Athenian democratic ideas. When he returned, Cimon was ostracized. Cimon had favored Athens' oligarchic adherents. The opposing faction now in power, was the democratic. A descendant of democracy's founder Cleisthenes, Pericles came to power in about 460.

Strategos

The office of military archon or strategos, usually translated into English as general, was elected. Pericles was elected strategos for the next 29 years.

The Long Walls

From about 458-56, Pericles had the Long Walls built between Athens and the Piraeus, a peninsula with three harbors about 4.5 miles from Athens.

Building Projects

Radical Democracy and Citizenship Law

Among the contributions made by Pericles to the Athenian democracy was the payment of magistrates. This was one reason the Athenians under Pericles decided to limit the people eligible to hold office. Only those born to two people of Athenian citizen status could henceforth be citizens and eligible. Children of foreign mothers would be excluded. Metic is the word for a foreigner living in the city. Since a metic woman couldn't produce citizen children, when Pericles had an affair with Aspasia of Miletus, he couldn't or, at least, didn't marry her.

Death of Pericles

In 430, the Spartans and their allies invaded Attica. At the same time a plague broke out in the overcrowded city to which the rural residents had fled. Pericles was suspended for the office of strategos. He was found guilty of theft and fined 50 talents. Because Athens still needed him, Pericles was then re-instated, but then, about a year after he lost his own two sons in the plague, Pericles died in the fall of 429, two and a half years after the Peloponnesian War began.

-- copied from About.com 9/9/13

-- product of N.S. Gill, a Latinist and freelance writer with a longtime focus on the classical world

Liberal Arts and Sciences in Athens

Philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy focused on the role of reason and inquiry. It had an important influence on modern philosophy, as well as modern science. The influence from ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophers was expanded to medieval Muslim philosophers and scientists, to the European Renaissance and Enlightenment, to the modern natural sciences and technology.

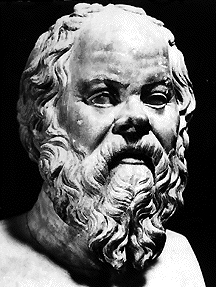

Socrates was a classical Greek philosopher. Considered one of the founders of Western philosophy, he strongly influenced Plato, and Aristotle. He made his most important contribution to Western thought through his method of inquiry. He is principally renowned for his contribution to the field of ethics, Socrates also lends his name to the concepts of Socratic irony and the Socratic Method. Socrates also made important and lasting contributions to the fields of epistemology and logic, and the influence of his ideas and approach, remains strong in providing a foundation for much western philosophy which followed.

Plato has the reputation of one of the most influential philosophers in Western thought. He wrote several dozen philosophical dialogues — arguments in the form of conversations — and a few letters. Though the early dialogues deal mainly with methods of acquiring knowledge, and most of the last ones with justice and practical ethics, his most famous works expressed a synoptic view of ethics, metaphysics, reason, knowledge, and human life. One can view Plato, with qualification, as an idealist and a rationalist.

Aristotle placed much more value on knowledge gained from the senses, and would correspondingly better earn the modern label of empiricist. Thus Aristotle set the stage for what would eventually develop into the scientific method centuries later. The works of Aristotle that still exist today appear in treatise form. The most important include Physics, Metaphysics, (Nicomachean) Ethics, Politics, De Anima (On the Soul), Poetics, and many others. Aristotle was a great thinker and philosopher, and his philosophy was crucial in governing intellectual thought in the Western world. His views and approaches dominated early Western science for almost 2000 years. As well as philosophy, Aristotle was a formidable inventor, and is credited with many significant inventions and observations.

Art

The art of ancient Greece has exercised an enormous influence on the culture of many countries from ancient times until the present. There are three scholarly distinctions of Greek art that correspond roughly with historical periods of the same names. These are the Archaic (700 - 480 BC), the Classical (480 - 323 BC) and the Hellenistic (323 – 31 BC) periods. The main physical categories of Greek art are sculpture, pottery, coin design and architecture.

The Greeks used many different types of materials in their sculptures including stone, marble and limestone as these were abundant in Greece. Other materials such as clay were also used but due to their brittle nature very few have survived. Greek sculptures are very important as the vast majority of them tell us a story about Gods, Heroes, Events, Mythical Creatures and Greek culture in general. Examples of Greek sculpture that survive and receive worldwide recognition are: the Parthenon Marbles, Agamemnon's Death Mask, stone statues of humans, such as the limestone Kouros (male) and Kore (female) statues (c.590 BC), Discobolos (The Discus Thrower) by Myron, the Venus de Milo and the Winged Victory of Samothrace.

The Ancient Greeks made pottery for everyday use, not for display; the trophies won at games, such as the Panathenaic Amphorae (wine decanters), are the exception. Most surviving pottery consists of drinking vessels such as amphorae, kraters (bowls for mixing wine and water), hydria (water jars), libation bowls, jugs and cups. Painted funeral urns have also been found. Miniatures were also produced in large numbers, mainly for use as offerings at temples.

Coins were mostly small disk-shaped lumps of gold, silver, or bronze, stamped with a geometric designs, -- symbols to indicate its city of origin or the god they were sacred to ---, and portraits -- of gods or heroes.

Architecture

Ancient Greek architects strove for the precision and excellence of workmanship that are the hallmarks of Greek art in general. The formulas they invented as early as the sixth century B.C. have influenced the architecture of the past two millennia.

Although the ancient Greeks erected buildings of many types, the Greek Temple best exemplifies the aims and methods of Greek architecture. The two principal orders in Archaic and Classical Greek temples architecture are the Doric and the Ionic.A third order of Greek architecture, known as the Corinthian, mostly common in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Representative temple of the Doric order is Parthenon, of the Ionic order is Erechtheum and of the Corinthian order is the temple of Zeus, all these temples sited in Athens.

The Greek Theater was a central place of formal gatherings in ancient Greece. Every Greek town had a theater. These were used for both public meetings as well as dramatic performances. These performances originated as religious ceremonies; they went on to assume their Classical status as the highest form of Greek culture by the 6th century BC. The theater was usually set in a hillside outside the town, and had rows of tiered seating set in a semicircle around the central performance area, the orchestra. Behind the orchestra was a low building called the skene, which served as a store-room, a dressing-room, and also as a backdrop to the action taking place in the orchestra. A number of Greek theaters survive almost intact, the best known being at the Ancient Theater of Epidaurus.

The architectural typology of the modern stadium derives from the classical prototype of the Greek Stadium. The Greek Stadium was the open space where footraces and other athletic contests took place in ancient Greece. The stadiums were usually U-shaped, the curve being opposite to the starting point. The courses were generally 600 Greek feet long (1 stadium), although the length varied according to local variations of the measuring unit. Natural slopes where used where possible to support the seats. The best known ancient Greek stadium is Kallimarmaron (Panathinaikon Stadium), sited in Athens.

Olympic Games

According to historical records, the first ancient Olympic Games can be traced back to 776 BC. They were dedicated to the Olympian gods and were staged on the ancient plains of Olympia, in the western part of the Peloponnese. They continued for nearly 12 centuries, until Emperor Theodosius decreed in 393 A.D. that all such “pagan cults” be banned.

The Olympic Games were closely linked to the religious festivals of the cult of Zeus, but were not an integral part of a rite. Indeed, they had a secular character and aimed to show the physical qualities and evolution of the performances accomplished by young people, as well as encouraging good relations between the cities of Greece. According to specialists, the Olympic Games owed their purity and importance to religion.

The ancient Olympic Games included the following events: pentathlon, running, jumping, discus throw, wrestling, boxing, pankration and equestrian events.

All free male Greek citizens were entitled to participate in the ancient Olympic Games, regardless of their social status. Married women were not allowed to participate in, or to watch, the ancient Olympic Games. However, unmarried women could attend the competition.

The Olympic victor received his first awards immediately after the competition. Following the announcement of the winner's name by the herald, a Hellanodikis (Greek judge) would place a palm branch in his hands, while the spectators cheered and threw flowers to him. Red ribbons were tied on his head and hands as a mark of victory. The official award ceremony would take place on the last day of the Games, at the elevated vestibule of the temple of Zeus. In a loud voice, the herald would announce the name of the Olympic winner, his father's name, and his homeland. Then, the Hellanodikis placed the sacred olive tree wreath, or kotinos, on the winner's head .

In 1859 Evangelos Zappas, a wealthy Greek philanthropist, sponsored the first modern international Olympic Games that were held in an Athens city square, with athletes from two countries: Greece and the Ottoman Empire. In June 23, 1894 Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and it was decided that the first IOC Olympic Games would take place in 1896 in Athens, as they did.

Pericles' Funeral Oration

Pericles' funeral oration is considered to be a valuable speech on the importance of democracy and a sneak peek into the way the people of Athens lived. It was given in the 5th-century by Pericles. His approach was an unusual way to give a funeral oration, and as such it has been immortalized and is still deeply valued. The Peloponnesian war had just begun, and the dead had been set out in tents for their families and the citizens of Athens to give them offerings before their burial. It was the custom at the time for somebody to be selected to give a funeral eulogy for all those killed in battle. The leader of Athens at the time, Pericles, was the one chosen to give the funeral speech after the first battles of the war. The war was in its infancy, and Pericles had a lot on his mind about the reasons that the war was taking place and what the soldiers he was speaking for had died to defend. He posed these thoughts to the citizens of Athens in order to allow them to celebrate with him the lives of the soldiers lost and the value of the democracy they were defending.

What Record Exists about what Pericles Said?

As with many of the orations given by the Greeks, the one given by Pericles was remembered mainly through paraphrasing the main idea of the speaker. Thucydides immortalized Pericles' funeral oration, and while it is impossible for the record to be one-hundred percent accurate, the goal of the speeches being recorded was to encompass the main idea the speaker was trying to convey as accurately as possible. There is said to be another speech given by Pericles during the Samian war, and his two speeches might actually be combined in Thucydides' records.

How did Pericles' Funeral Oration Differ from the Way they Were Typically Given?

The speech Pericles gave was critical of certain customs of Athens. Pericles said in his funeral oration that it should not be the responsibility of one person giving a funeral oration to give the citizens and a warrior's family the final impression of the fallen soldier's honor and reputation. He plainly disliked the fact that the custom declared one person to send off those who had fallen in battle and that that person's opinion could mar the reputations of the dead. His exact phrase on the matter was, "And I could have wished that the reputations of many brave men were not to be imperiled in the mouth of a single individual, to stand or fall as he spoke well or ill."

On the one hand, the friend who is familiar with every fact of the story may think that some point has not been set forth with that fullness which he wishes and knows it to deserve; on the other, he who is a stranger to the matter may be lead by envy to suspect exaggeration if he hears anything above his own nature.

What did Pericles Find Worth Praising about Athens if Not the Military Victories?

Pericles wanted to make sure the people of Athens looked carefully at the quality of life they were leading and consider what it was about their home that was worth protecting. Pericles went on to list the several qualities about Athens that he thought were extraordinary and advanced about their civilization. He found it incredible that their ancestors and fathers had built the nation from the ground up and supported the needs and interests of the many rather than the few. He found democracy to be extremely powerful and important in shaping a powerful nation. He emphasized the freedom the citizens of Athens were able to experience and how they were given opportunities to relax when they were done with their work and participate in games and entertainment as well as chances to have prosperous businesses. Pericles was proud of the fact that the people of Athens embodied a "live and let live" philosophy, where they allowed anybody within their borders and didn't complain if others held different interests and values. He was also very impressed that despite this, the citizens were always ready to face and drive away danger and that their military was always strong and prepared for battle.

What was Pericles' Main Message to the Athenians?

Pericles wanted to give the Athenians pride in their country. He wanted to show them that they had something special to defend that other countries didn't have, and that is what made them so great. He wanted them to remember their dead with honor and respect, and in doing so, he also was able to show the citizens the strengths of their democracy and the power that the love they had for their nation and way of life was able to provide. Pericles gave them a sense of pride in their deeds and a boost in morale that would be greatly needed throughout the rest of the duration of the Peloponnesian war. Pericles' funeral oration was a powerful speech that illuminated the significance of the sacrifices made by the soldiers to uphold the unique democracy in the land of Athens.

Pericles' funeral oration was an incredibly significant speech that glorified the lifestyle of the citizens of Athens and outlined what made it such a strong nation. Pericles made sure to touch upon the truest way to properly honor those who had fallen in battle defending the Athenian way of life. In doing so, he was able to deliver a powerful speech that has resonated with people for centuries afterward. In his unique approach to the funeral eulogy of the soldiers, Pericles was able to bring light to the dangers of the custom of letting one man decide how the rest of history would view the fallen soldiers, elaborate on the greatness of Athens and how its opportunities created an environment worth protecting and provided much needed comfort to the bereaved citizens and families of the fallen soldiers. Pericles' funeral oration is presented in full in Thucydides' second book on the history of the Peloponnesian war.

Copied from History Answers 9/9/13

Reflections on Pericles and Democracy

Let’s take an objective look at Pericles defense of democracy and separate political rhetoric and the occasion of a funeral from the reality of the Athenian Polis in 431 B.C. It was a stirring speech, designed to honor the dead and motivate the living in a time of war – a war that would last another twenty-seven years.

When it is a question of settling private disputes, everyone is equal before the law: when it is a question of putting one person before another in positions of public responsibility, what counts is not membership of a particular class, but the actual ability which the man possesses.

The Athenian Polis was a balance between branches of a government -- Archons, Council of 500 and Assembly. The Archons were the “wise men” elected from the aristocratic class for one year. The Council of 500 were chosen by lot from nominees of the people and also served for one year. The Assembly was made up of all male citizens. The council introduced new laws which were voted on by the assembly, while the archons acted as government administrators. This system was designed to allow broad participation and prevent the accumulation of power.

The court system was made up of non-professionals organized to facilitate fair trials of accused citizens. Common citizens served as jurors and members of the appeals court.

Did Pericles correctly describe Athenian society? Yes, if we’re speaking of the rights of citizens. I would say its as accurate as labeling the United States as a democracy. Not all citizens and classes are satisfied with their political system at any one time, but when the many classes can be balanced in a way that creates stability, it becomes successful.

I declare that our city is an education to Greece, and I declare that in my opinion each single one of our citizens, in all the manifold aspects of life, is able to show himself the rightful lord and owner of his own person, and do this, moreover, with exceptional grace and exceptional versatility. And to show that this is no empty boasting for the present occasion, but real tangible fact, you have only to consider the power which our city possesses and which has been won by those very qualities which I have mentioned. Athens, alone of the states we know, comes to her testing time in a greatness that surpasses what was imagined of her. In her case, and in her case alone, no invading enemy is ashamed at being defeated, and no subject can complain of being governed by people unfit for their responsibilities. Mighty indeed are the marks and monuments of our empire which we have left. Future ages will wonder at us, as the present age wonders at us now. We do not need the praises of a Homer, or of anyone else whose words may delight us for the moment, but whose estimation of facts will fall short of what is really true. For our adventurous spirit has forced an entry into every sea and into every land; and everywhere we have left behind us everlasting memorials of good done to our friends or suffering inflicted on our enemies.

Pericles is right to say that Athens exceeded what was expected of her, because they knew they had gone where no political system had gone before. They had created a complex agrarian society with citizen participation in government and laws to protect the people.

Two caveats apply here, however. Pericles ignores the might of Sparta during a time when the two Poleis were at war. He derides the unique Spartan oligarchy which, in fact, was successful as a rival political system. Secondly, he hides Athenian imperialism under the cloak of “adventurous spirit.” Imperialism was a direct cause of the Peloponnesian War which Athens would lose.

What I would prefer is that you should fix your eyes every day on the greatness of Athens as she realty is, and should fall in love with her. When you realize her greatness, then reflect that what made her great was men with a spirit of adventure, men who knew their duty, men who were ashamed to live below a certain standard. If they ever failed in an enterprise, they made up their minds that at any rate the city should not find their courage lacking to her, and they gave to her the best contribution that they could. They gave her their lives, to her and to all of us, and for their own selves they won praises that never grow old.

These statements reflect the confidence and pride of Athens. That pride supported free thinkers who moved the culture forward and the soldiers that defended her.

I couldn’t help thinking of the colonial spirit used to describe the early United States. People came to North America because of their adventurous spirit. The west was settled by the same motivation. Sadly, much of this spirit has been compromised in the post-modern world as we dumb it down for the sake of socialist ideals. The Athenians would point out that we are tearing down, block by block, that which made us great – liberty.

For famous men have the whole earth as their memorial: it is not only the inscriptions on their graves in their own country that mark diem out; no, in foreign lands also, not in any visible form but in people's hearts, their memory abides and grows. It is for you to try to be like them. Make up your minds that happiness depends on being free, and freedom depends on being courageous.”

Pericles made the point that wars are a part of life and having the courage to fight and win is the only guarantee of freedom. This is another way of stating that which made Athens excel – it was a society that provided the freedom and encouragement to be seek happiness through pursuing one’s interests. A philosopher could be a philosopher, and was encouraged in the effort, rather than being a goods producer. When people are allowed to uses the tools they are born with, rather than being stifled by economics, they contribute more to the advancement of their culture.

Copied from Mike Anderson 9/10/13

The Athenian Empire - The First Naval Empire

From The Delian League To The Athenian Empire

-- by Thomas Nash

When Athens began to emerge as a Greek city state in the ninth century, it was a poor city, built on and surrounded by undesirable land, which could support only a few poor crops and olive trees. As it grew it was forced to import much of its food, and while it was near the center of the Greek world, it was far from being a vital trading juncture like, for example, Corinth. It's army was, by the standards of cities such as Sparta, weak. Yet somehow it became the most prominent of the Greek city states, the one remembered while contemporaries such as Sparta are often forgotten. It was the world's first democracy of a substantial size (and, in some ways, though certainly not others, one of the few true democracies the world has ever seen), producing art and fine architecture in unprecedented amounts. It became a centre of thinking and literature, producing philosophers and playwrights like Socrates and Aristophanes. But most strikingly of all, it was the one Greek city that managed to control an empire spanning the Aegean sea. During the course of this essay I will attempt to explain how tiny Athens managed to acquire this formidable empire, and why she became Greece's most prominent city state, rather than cities which seemed to have more going for them like Sparta or Corinth.

The Persian Invasions and Birth of the Delian League

While we tend to think of Greece as the most important nation of the ancient world before Rome, it was in fact a haphazard collection of autonomous city states, which, even when their forces were combined, were on paper no match for mighty empires like that of Persia. So, when the Persian King Darius I invaded, the Greeks must have been more than a little alarmed. Infuriated by an Athenian-backed revolt in Ionia (the stretch of Turkey's west coast colonised by Ionian Greeks, a historic group which included the Athenians), Darius had demanded tokens of submission from the Greek states. While most of the smaller cities gave in, Athens and Sparta refused to do so, killing the foreign King's heralds as a gesture of defiance. Athens' actions showed a great deal of pluck, given it's relative military weakness, and enraged Darius. He put together a mighty expeditionary force and set sail in 490 B.C.

The Spartan army proceeded to the plain of Marathon near Athens. The Spartans could not help as news of the Athenians' plight reached them on a religious holiday. However, the Athenians managed to win a convincing victory, faced with an army three times the size of theirs. When Darius' son, Xerxes, amassed one of the greatest armies of antiquity to exact revenge for his father's humiliation, fewer than 400 Greek vessels defeated the 1,200 strong Persian fleet thanks to the clever command of the Athenian statesman Themistocles. This caused Xerxes to flee to Asia, and in 479 B.C. his army followed him, pulling out of Greece.

By this time Athens had won the friendship of many Greek states, both because of their defeat of the Persians and because of the unpopularity of the Spartan regent, Pausanias, who, according to Thucydides, had "begun to reveal the true arrogance of his nature ... [and] appeared to be trying to set himself up as dictator." Thucydides tells us that for these reasons the city states "had gone over to the side of the Athenians", which proceeded to take over leadership of the Delian League, a confederacy of cities determined to protect themselves from Persian attack and "compensate themselves for their losses by ravaging the territory of the king of Persia." Sparta was happy to cede leadership of the league as (according to Thucydides) "they were afraid any other commanders they sent abroad would be corrupted, as Pausanias had been, and they were glad to be relieved of the burden of fighting the Persians.... Besides, at the time they still thought of the Athenians as friendly allies." Also, Sparta wished to keep its army at home to deal with helot revolts (and also to prevent its soldiers from becoming corrupted).

Initially the Delian League was a fairly loose coalition of states, each one independent and sharing a common interest with the others. Members of the league were numerous: Thucydides tells us that they included "Chios, Lesbos, Plataea ... most of Acarnania ... Ionia, the Hellespont, Thrace and the islands between the Peloponnese and Crete towards the East, and all the Cyclades except for Melos and There" as well as Aegina and most of the Euboean cities. Together, these states constituted a formidable force capable of achieving it's objectives.

A map showing the Athenian Empire

(Courtesy 'Brewminate' )

While Athens was the leader of the league, all its member states had an equal vote in the ruling council. Initially the league's actions were only for the well being of its members. Under the command of the Athenian Cimon, the Persian fortress of Eion on the Thracian coast was captured in 476 B.C. After this, Persian power in the North began to diminish. In 473 B.C Cimon crushed a group of Dolopian pirates who had been terrorising the central Aegean from the island of Scyros. An allied colony was established in their place. In 468 B.C. the Persian fleet was annihilated on the river Eurymedon in southern Turkey, again by Cimon, while at some point in the 460s, Cimon liberated the Southern Aegean and Caria from Persian control.

Meanwhile, Sparta was in trouble. Two of the states in the Peloponnesian League, a Spartan-led collection of states far looser than the Delian league, became democratic, while Argos revolted against her leadership. After a devastating earthquake and helot revolt, the stricken Spartans appealed to Athens for help. This was only given with reluctance after Cimon begged the Athenians "not to allow Greece to go lame, or their own city to be deprived of its yoke-fellow". However, Sparta grew alarmed by growing Athenian imperialism and asked that the Athenian presence in their city be withdrawn.

From a league to an empire

While freeing the southern Aegean from Persian control, Cimon succeeded in convincing more states to join the league. According to Diodorus, having persuaded "the cities of the sea coast [and] the cities of Lycia" to revolt, he "took them over in the same way". This, along with further evidence, suggests that these cities were forced to join whether or not they wanted to. Plutarch tells us "Phaselis ... refused to admit [Cimon's] fleet or to fight against the King, and so he devastated their land." In 480 B.C. the Athenians attempted to force impoverished Andros to pay a sum to the league:

"the Greeks ... surrounded Andros with a view to capturing it. Andros was the first island to reject Themistokles' requests for money."

(Herodotus VIII.111)

Further evidence of expansionistic Athenian policy can be seen in the case of Carystus, the one city in Euboea which declined membership of the Delian League. After refusing to join a second time in 472 B.C., they were paid a visit by the league's fleet and promptly conquered. In both these cases the Athenian's actions were at least partially justifiable. The Athenians had secured Greek control of the Aegean and Carian. At the time of the Carystian incident the Persians still controlled these regions, and thus Carystus could become a stepping stone to mainland Greece and encourage other Euboean cities to leave the league.

A less justifiable incident was the way the Athenians dealt with Naxos' attempted secession from the league. The Naxians had seen the Persian threat in the North decline as a result of the league's actions, and saw no reason to continue contributing money to the league. The Athenians and the other allies, however, did not see it that way. The Naxians' resources were needed in the South and the Naxians had, after all, sworn to remain in the league forever, as symbolised by the sinking of lumps of metal in the sea: a permanent, irreversible action. Athens also had reasons of its own, which I gesture at in my conclusion. Naxos was subjugated and the allies decided to take its fleet and change the naval contributions it made into a regularly-given tribute. A garrison was left behind: Naxos effectively became an imperial subject. Similarly, Erythrai, which rebelled in the 450's B.C. was the subject of a harsh and authoratitive decree.

By now the Persian threat had more or less dissolved and so the league had achieved its purpose. However the Athenians chose to enforce the league's oath and force all members to remain in it. One member to revolt was Thasos, a rich and navally powerful island which controlled parts of nearby Thrace. The Athenians clearly had their eyes set on natural resources in Thrace, and when they started to dispute the Thasian possession of a gold mine, the Thasians grew worried, and threatened to withdraw from the league.

Because of this the league overcame the Thasian fleet in 465 B.C. capturing 33 ships and laid siege to Thasos. The Spartans were sufficiently concerned with Athenian expansionism (and while the Delian League acted as one unit, it was clear that the Athenians were behind this action) to sign a secret pact with the Thasians under which they would invade Attica. As it happened Sparta could not do this due to internal strife, but the pact shows how transparent the Athenian imperialism was.

At the same time as besieging Thasos the Athenians established an allied colony in Thrace, where they were clearly anxious to establish a foothold. In 462 B.C. Thasos had to capitulate, and lost her fleet, gold mint and city walls. Like Naxos, it was forced to pay tribute rather than making contributions to the navy. The disputed gold mine and some other valuable settlements in Thrace were annexed by the Athenians (it is notable that the Athenians took these over without even a pretence to them being under control of all the league).

Athens embarked on an aggressive new foreign policy, aimed against Sparta, Athens' major rival in Greece. Athens allied with Argos, Sparta's traditional antagonist in the Peloponnese, and proceeded to attack Corinth, Sparta's most important ally. Vast operations were launched on both land and sea, and the result was that by 457 B.C. Athens had control of the whole of central Greece (although this control had collapsed by the time of the Thirty Year Truce's signing in 445 B.C.). Athens' eagerness to build an empire (and the fact that the sometimes-foolish boldness with which it acted was partly caused by its being a democracy) was evident in its decision to send a vast fleet of 200 triremes to aid an Egyptian revolt against the Persian empire. This served little practical purpose, and more sober minds would doubtless have kept to their own affairs. Athenian cleruchies (colonies) were set up at strategic points throughout Greece, the Mediterranean and even the Black sea, where Athens maintained a good relationship with Cimmerians as it grew more and more dependent on the import of grain from this tribe. Amphipolis was built at a strategic junction on the northern Aegean coast road; Thourioi was founded as an Athenian stronghold in Magna Graecia; and a fleet was sent to the Back Sea simply as a demonstration of Athenian power and to keep the vital trade routes open. An Athenian empire was now well and truly established.

The Resultant Empire

Athens had by now obtained a mighty empire. Of the more than 200 members (membership of the league had increased because Athens' friendship was an important asset for many Greek cities), only a few allies remained largely autonomous. According to Aristotle:

"After the Athenians had gained their empire, they treated their allies rather dictatorially, except for Chios, Lesbos and Samos. These they regarded as guardians of the empire, allowing them to keep their own constitution and rule over any subjects they happened to have."

(Consitution of Athens XXIV)

However, the majority had ceased to contribute ships and instead gave Athens tribute. The change can be seen in the transmutation of the word phoros' meaning. Originally it meant 'contribution', but as the Delian League changed into the Athenian Empire, it came to mean 'tribute.' In around 448 B.C. Athens issued a controversial decree:

"If anyone in the cities strikes silver coins and does not use the currency, weights and measures of the Athenians, but foreign currency, weights and measures ... exact penal retribution."

(Klearkhos Decree)As well as using the tribute it received to build ships, Athens embarked on an ambitious building program under Pericles. The Acropolis was rebuilt, with magnificent buildings such as the Parthenon (shown below) and Erechtheum contributing to the beautification of the city. Some warned that by doing this, the Athenians gave up any pretence of working for the good of the League. The allies were indeed furious at the way their money was spent, but Pericles replied that so long as Athens protected her allies from the Persians it was not their concern how their money was spent

The Parthenon (Courtesy Encyclopedia Britannica)

The Parthenon (Courtesy Encyclopedia Britannica)

Athens maintained it's leadership by a number of means. It possessed a magnificent navy, as the League's ships became part of the Athenian navy. This consisted of 300 triremes, and was by far the largest in the Greek world. At least 60 triremes were kept in the Aegean at any one time. The trireme was the predominant warship of the time, a narrow vessel built for speed. Each one required 180 oarsmen in three tiers, and fought by ramming enemy ships or boarding them with marines. As Pericles said to the Athenians:

"The whole world is divided into two parts, the sea and the land... Of the whole of one part you are in control"

(Thucydides II.62)

Thucydides also tells us of the extent of the Atenians' power over their discontented but impotent allies:

"The subject states of Athens were especially eager to revolt, even though it was beyond their capability."

(Thucydides VIII.2)

"They learned nothing from the fate of those of their neighbours who had already revolted and been subdued."

(Thucydides III.39)

"The Athenian fleet grew strong with the money which the allies had themselves contributed, whilst whenever they revolted they were ill-prepared and inexperienced."

(Thucydides I.99)

Athens maintained a tight grip over all their allies, never letting a hint of dissent go unpunished. For example, the Chalkians had to swear not to "follow anyone who revolts, and if any person causes a revolt, [to] denounce him to the Athenians." Often, constitutions that were models of Athens' were imposed on allies, and serious cases were placed under the jurisdiction of Athens. Law courts often prosecuted anti-Athenian elements. Control became so absolute that eventually no ally could sentence someone to death without first obtaining Athenian permission. We are told that:

"...the Athenians sail out and bring false charges against the respectable elements among [their allies] and hate them, because they realize that the ruler is always hated by the subject"

(Old Oligarch I.14)

It is worth noting that many Athenians viewed this as an altruistic arrangement, and could not understand the anger at lost independence it caused. As Athenian delegates to Sparta complained:

"In law suits with our allies arising out of contracts, we have put ourselves at a disadvantage, and when we arrange to have such cases tried by imperial courts at Athens, people accuse us of being over-fond of going to law."

(Thucydides I.77)

Colonies established on confiscated land were useful in the control of troublesome allies:

"Pericles sent out one thousand settlers to the Khersonese, five hundred to Naxos, 250 to Andros, one thousand to Thrace to make their homes with the Bisaltai ... and, by setting up garrisons among the allies, to implant a fear of rebellion."

(Plutarch, Pericles XI)

Athens opportunistically exploited religion and idealism. Land was claimed because it had belonging to Athena, the patron of Athens, or, in the case of Scyros, because Theseus' bones were claimed to have been found there. Athens encouraged the belief that she was the mother of all Ionian cities, and propagated the myth that the Athenian Demeter had granted corn to mankind. While Athens usually supported democrats against oligarchs, she would occasionally support oligarchs when the situation demanded it. In short, she was willing to do practically anything to maintain her empire, and went to extreme lengths. The Delian League had been intended to keep Greece from becoming a part of the Persian empire. Instead, it was the means by which Athens established an empire in Greece.

Conclusion

When she assumed leadership of the Delian League, Athens' intentions were for the most part honourable. In the first few years of her hegemony she accomplished extraordinary feats, forcing the Persians from Greece. However, she also experienced a huge influx of money from the league's members intended to pay for its naval forces. The Athenians grew used to a higher standard of living, due to the money and food now flowing into the city. The prestige and power of their city was advantageous to them all. Athens was reliant on imported corn to support her growing population: the money now flowing into her coffers enabled her to obtain it. Income from tributes and pillaging from the empire came to more than a thousand talents a year, while confiscated land and colonies provided livelihoods for many Athenians. The money from the empire was used to support the navy, construct magnificent public buildings, and support the city's poor. Jobs were created by the empire as well: almost everyone served in the navy at one point or another.

Everyone in the city benefited, so it is not surprising that democratic Athens elected to keep the money flowing in when the league succeeded in eliminating the Persian threat. While justifying their actions to the Peloponnesians, Athenian representatives said.

"We have done nothing surprising, nothing contrary to human nature, if we accepted leadership when it was offered and are now unwilling to give it up."

(Thucydides I.76)

"So far as the favor of the gods is concerned, we think we have as much right to that as you ... it is a general and necessary law of nature to govern wherever one can ... we know that you or anybody else with the same power as ours would be acting in precisely the same way."

(Thucydides V.105)

It is also worth noting that while the tributes became more oppressive after the Peace of Callias, they were never seen as being far too high. In fact the only dramatic rise in their level took place in 425 B.C., and this was both because of the political tension that year and to correct for recent inflation. Athens' preference for monetary rather than naval contributions was also at least partially justified by the fact that it was beyond the capabilities of many of the states in the Delian League to build triremes and train crews in the complicated art of manoeuvring a triple-banked rowing boat in battle. Athens had plenty of men eager to earn money as oarsmen, and also the shipyards and skilled craftsmen required to build triremes. Indeed, many in the league were happy to let Athens take care of building ships.

However, by doing this they were signing away their independence. The fleet which was meant to be the league's became Athens', and with it she could overcome any ally who complained about the tribute it had to pay. It could be argued that Athens' rashness, its self-confidence and the notorious "busy-bodyness" of which the Spartans complained were partly due to its democratic status. While oligarchs might not have taken such risks, the assembly was pushed into adventurism time and again by the potential rewards it held for the city's people. They knew their empire for what it was, but were naturally loath to give up the prosperity, wealth, prestige and security that came with it. The latter concern in particular provided a self-perpetuating rationale, as each exercise in imperialism infuriated the city's traditional enemies, and its erstwhile allies, further. As Pericles said to his countrymen:

"Your empire is now a tyranny: it may have been wrong to take it; it is certainly dangerous to let it go."

(Thucydides II.63)

Bibliography

- Athens Ascendant, George Dent Wilcoxon (Iowa State Press/1979)

- History of the Peloponessian War, Thucydides (Primary source)

- A History of Greece, Bury & Meiggs (MacMillan, 1975)

- The Athenian Empire, Meiggs (OUP, 1972)

- The Athenians And Their Empire, McGregor (University of British Columbia Press, 1987)

- These Were the Greeks, Amos & Lang (Stanley Thornes, 1979)

-- copied from Thomas Nash © 2000

<http://www.bigissueground.com/history/ash-athenianempire.shtml> (9/9/13)

The Trial & Death of Socrates

The trial and execution of Socrates in Athens in 399 B.C.E. puzzles historians. Why, in a society enjoying more freedom and democracy than any the world had ever seen, would a seventy-year-old philosopher be put to death for what he was teaching? The puzzle is all the greater because Socrates had taught--without molestation--all of his adult life. What could Socrates have said or done than prompted a jury of 500 Athenians to send him to his death just a few years before he would have died naturally?

Finding an answer to the mystery of the trial of Socrates is complicated by the fact that the two surviving accounts of the defense (or apology) of Socrates both come from disciples of his, Plato and Xenophon. Historians suspect that Plato and Xenophon, intent on showing their master in a favorable light, failed to present in their accounts the most damning evidence against Socrates.

What appears almost certain is that the decisions to prosecute and ultimately convict Socrates had a lot to do with the turbulent history of Athens in the several years preceding his trial. An examination of that history may not provide final answers, but it does provide important clues.

Background

Socrates, the son of a sculptor (or stonecutter) and a midwife, was a young boy when the rise to power of Pericles brought on the dawning of the "Golden Age of Greece." As a young man, Socrates saw a fundamental power shift, as Pericles--perhaps history's first liberal politician--acted on his belief that the masses, and not just property-owning aristocrats, deserved liberty. Pericles created the people's courts and used the public treasury to promote the arts. He pushed ahead with an unprecedented building program designed not only to demonstrate the glory that was Greece, but also to ensure full employment and provide opportunities for wealth creation among the unpropertied class. The rebuilding of the Acropolis and the construction of the Parthenon were the two best known of Pericles' many ambitious building projects.

Growing to adulthood in this bastion of liberalism and democracy, Socrates somehow developed a set of values and beliefs that would put him at odds with most of his fellow Athenians. Socrates was not a democrat or an egalitarian. To him, the people should not be self-governing; they were like a herd of sheep that needed the direction of a wise shepherd. He denied that citizens had basic virtue necessary to nurture a good society, instead equating virtue with a knowledge unattainable by ordinary people. Striking at the heart of Athenian democracy, he contemptuously criticized the right of every citizen to speak in the Athenian assembly.

Writing in the third-century C.E. in his The Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laertius reported that Socrates "discussed moral questions in the workshops and the marketplace." Often his unpopular views, expressed disdainfully and with an air of condescension, provoked his listeners to anger. Laertius wrote that "men set upon him with their fists or tore his hair out," but that Socrates "bore all this ill-usage patiently."

We get one contemporary view of Socrates from playwright Aristophanes. In his play Clouds, first produced in 423 B.C.E., Aristophanes presents Socrates as an eccentric and comic headmaster of a "thinkery" (or "thoughtery"). He is portrayed "stalking the streets" of Athens barefoot, "rolling his eyes" at remarks he found unintelligent, and "gazing up" at the clouds. Socrates at the time of Clouds must have been perceived more as a harmless town character than as a serious threat to Athenian values and democracy. Socrates himself, apparently, took no offense at his portrayal in Clouds. Plutarch, in his Moralia, quoted Socrates as saying, "When they break a jest upon me in the theatre, I feel as if I were at a big party of good friends." Plato, in his Symposium, describes Socrates and Aristophanes engaged in friendly conversation.

Other plays of the time offer additional clues as to the reputation of Socrates in Athens. Comic poet Eupolis has one of his characters say: "Yes, and I loathe that poverty-stricken windbag Socrates who contemplates everything in the world but does not know where his next meal is coming from." Birds, a play of Aristophanes written six years after his Clouds, contains a revealing reference. Aristophanes labels a gang of pro-Sparta aristocratic youths as "Socratified." Sparta--the model of a closed society--and Athens were enemies: the remark suggests Socrates' teaching may have started to be seen as subversive by 417 B.C.E.

The standing of Socrates among his fellow citizens suffered mightily during two periods in which Athenian democracy was temporarily overthrown, one four-month period in 411-410 and another slightly longer period in 404-403. The prime movers in both of the anti-democratic movements were former pupils of Socrates, Alcibiades and Critias. Athenians undoubtedly considered the teachings of Socrates--especially his expressions of disdain for the established constitution--partially responsible for the resulting death and suffering. Alcibiades, perhaps Socrates' favorite Athenian politician, masterminded the first overthrow. (Alcibiades had other strikes against him: four years earlier, Alcibiades had fled to Sparta to avoid facing trial for mutilating religious pillars -- statues of Hermes -- and while in Sparta had proposed to that state's leaders that he help them defeat Athens.) Critias, first among an oligarchy known as the "Thirty Tyrants," led the second bloody revolt against the restored Athenian democracy in 404. The revolt sent many of Athen's leading democratic citizens (including Anytus, later the driving force behind the prosecution of Socrates) into exile, where they organized a resistance movement.

Critias, without question, was the more frightening of the two former pupils of Socrates. I.F. Stone, in his The Trial of Socrates, describes Critias (a cousin of Plato's) as "the first Robespierre," a cruel and inhumane man "determined to remake the city to his own antidemocratic mold whatever the human cost." The oligarchy confiscated the estates of Athenian aristocrats, banished 5,000 women, children, and slaves, and summarily executed about 1,500 of Athen's most prominent democrats.

One incident involving Socrates and the Thirty Tyrants would later become an issue at his trial. Although the Thirty normally used their own gang of thugs for such duties, the oligarchy asked Socrates to arrest Leon of Salamis so that he might be executed and his assets appropriated. Socrates refused to do so. Socrates would point to his resistance to the order as evidence of his good conduct. On the other hand, Socrates neither protested the decision nor took steps to warn Leon of Salamis of the order for his arrest--he just went home. While good citizens of Athens were being liquidated right and left, Socrates--so far as we know--did or said nothing to stop the violence.

The horrors brought on by the Thirty Tyrants caused Athenians to look at Socrates in a new light. His teachings no longer seemed so harmless. He was no longer a lovable town eccentric. Socrates--and his icy logic--came to be seen as a dangerous and corrupting influence, a breeder of tyrants and enemy of the common man.

The Trial

A general amnesty issued in 403 meant that Socrates could not be prosecuted for any of his actions during or before the reign of the Thirty Tyrants. He could only be charged for his actions during the four years preceding his trial in 399 B.C.E. It appears that Socrates, unchastened by the antidemocratic revolts and their aftermaths, resumed his teachings and once again began attracting a similar band of youthful followers. The final straw may well have been an another antidemocratic uprising--this one unsuccessful--in 401. Athens finally had enough of "Socratified" youth.

In Athens, criminal proceedings could be initiated by any citizen. In the case of Socrates, the proceedings began when Meletus, a poet, delivered an oral summons to Socrates in the presence of witnesses. The summons required Socrates to appear before the legal magistrate, or King Archon, in a colonnaded building in central Athens called the Royal Stoa to answer charges of impiety and corrupting the youth. The Archon determined--after listening to Socrates and Meletus (and perhaps the other two accusers, Anytus and Lycon)--that the lawsuit was permissible under Athenian law, set a date for the "preliminary hearing" (anakrisis), and posted a public notice at the Royal Stoa.

The preliminary hearing before the magistrate at the Royal Stoa began with the reading of the written charge by Meletus. Socrates answered the charge. The magistrate questioned both Meletus and Socrates, then gave both the accuser and defendant an opportunity to question each other. Having found merit in the accusation against Socrates, the magistrate drew up formal charges. The document containing the charges against Socrates survived until at least the second century C.E. Diogenes Laertius reports the charges as recorded in the now-lost document:

This indictment and affidavit is sworn by Meletus, the son of Meletus of Pitthos, against Socrates, the son of Sophroniscus of Alopece: Socrates is guilty of refusing to recognize the gods recognized by the state, and of introducing new divinities. He is also guilty of corrupting the youth. The penalty demanded is death.

The trial of Socrates took place over a nine-to-ten hour period in the People's Court, located in the agora, the civic center of Athens. The jury consisted of 500 male citizens over the age of thirty, chosen by lot. Most of the jurors were probably farmers. The jurors sat on wooden benches separated from the large crowd of spectators--including a twenty-seven-year-old pupil of Socrates named Plato--by some sort of barrier or railing.

Guilt Phase of Trial

The trial began in the morning with the reading of the formal charges against Socrates by a herald. The prosecution presented its case first. The three accusers, Meletus, Anytus, and Lycon, had a total of three hours, measured by a waterclock, to present from an elevated stage their argument for guilt. No record of the prosecution's argument against Socrates survives.

Easily the best known and most influential of the three accusers, Anytus, is widely believed to have been the driving force behind the prosecution of Socrates. Plato's Meno offers a possible clues as to the animosity between Anytus, a politician coming from a family of tanners, and Socrates. In the Meno, Plato reports that Socrates' argument that the great statesmen of Athenian history have nothing to offer in terms of an understanding of virtue enrages Anytus. Plato quotes Anytus as warning Socrates: "Socrates, I think that you are too ready to speak evil of men: and, if you will take my advice, I would recommend you to be careful." Anytus had an additional personal gripe concerning the relationship Socrates had with his son. Plato quotes Socrates as saying, "I had a brief association with the son of Anytus, and I found him not lacking in spirit." It is not known whether the relationship included sex, but Socrates--as were many men of the time in Athens--was bisexual and slept with some of his younger students. Anytus almost certainly disapproved of his son's relationship with Socrates. Adding to the displeasure of Anytus must have been the advice Socrates gave to his son. According to Xenophon, Socrates urged Anytus's son not to "continue in the servile occupation [tanning hides] that his father has provided for him." Without a "worthy adviser," Socrates predicted, he would "fall into some disgraceful propensity and will surely go far in the career of vice."

It is a matter of dispute among historians whether the accusers focused more attention on the alleged religious crimes, or the alleged political crimes, of Socrates. I. F. Stone attaches far more significance to the political crimes, while other historians such as James A. Colaiaco, author of Socrates Against Athens, give more weight to the charge of impiety.

I. F. Stone argues that "Athenians were accustomed to hearing the gods treated disrespectfully in both the comic and tragic theatre." He points out that Aristophanes, in his Clouds, had a character speculating that rain was Zeus urinating through a sieve, mistaking it for a chamberpot--and that no one ever bothered to charge Aristophanes with impiety. Stone concludes: "One could in the same city and in the same century worship Zeus as a promiscuous old rake, henpecked and cuckolded by Juno or as Justice deified. It was the political, not the philosophical or theological, views of Socrates which finally got him into trouble."

Important support for Stone's conclusion comes from the earliest surviving reference to the trial of Socrates that does not come from one of his disciples. In 345 B.C.E., the famous orator Aechines told a jury: "Men of Athens, you executed Socrates, the sophist, because he was clearly responsible for the education of Critias, one of the thirty anti-democratic leaders."

James Colaiaco's conclusion that impiety received more prosecutorial attention than did political sins rests on Plato's Apology. Colaiaco sees Plato's famous account of the defense of Socrates as being--although far from a verbatim transcription of the words of Socrates--fairly representative of the major points of his defense. He notes that Plato wrote the Apology within a few years of the trial and must have expected many of his readers to have firsthand knowledge of the trial. Why, Colaiaco asks, would have Plato misrepresented the arguments of Socrates, or hid key elements of the prosecution's case, when his actions in doing so could so easily be exposed? Since the Apology seems to give great weight to the charge of impiety--and relatively little weight to the association of Socrates with the Thirty Tyrants--Colaiaco assumes this must have been a fair reflection of the trial. At the same time, Colaiaco recognizes that because of the association of Socrates with Critias "the prosecution could expect any Athenian jury to harbor hostile feelings toward the city's gadfly."

Piety had, for Athenians, a broad meaning. It included not just respect for the gods, but also for the dead and ancestors. The impious individual was seen as a contaminant who, if not controlled or punished, might bring upon the city the wrath of the gods--Athena, Zeus, or Apollo--in the form of plague or sterility. The ritualistic religion of Athens included no scripture, church, or priesthood. Rather, it required--in addition to belief in the gods-- observance of rites, prayers, and the offering of sacrifices.

Any number of words and actions of Socrates may have contributed to his impiety charge. Preoccupied with his moral instruction, he probably failed to attend important religious festivals. He may have stirred additional resentment by offering arguments against the collective, ritualistic view of religion shared by most Athenians or by contending that gods could not, as Athenians believed, behave immorally or whimsically. Xenophon indicates that the impiety charge stemmed primarily from the contention of Socrates that he received divine communications (a "voice" or a "sign") directing him to avoid politics and concentrate on his philosophic mission. A vague charge such as impiety invited jurors to project their many and varied grievances against Socrates.

Dozens of accounts of the three-hour speech (apologia) by Socrates in his defense existed at one time. Only Plato's and Xenophon's accounts survive. The two accounts agree on a key point. Socrates gave a defiant--decidedly unapologetic--speech. He seemed to invite condemnation and death.

Plato's apology describes Socrates questioning his accuser, Meletus, about the impiety charge. Meletus accuses Socrates of believing the sun and moon not to be gods, but merely masses of stone. Socrates responds not by specifically denying the charge of atheism, but by attacking Meletus for inconsistency: the charge against him accused him of believing in other gods, not in believing in no gods. If Plato's account is accurate, Socrates could have been seen by jurors offering a smokescreen rather than a refutation of the charge of impiety.

Plato's Socrates provocatively tells his jury that he is a hero. He reminds them of his exemplary service as a hoplite in three battles. More importantly, he contends, he has battled for decades to save the souls of Athenians--pointing them in the direction of an examined, ethical life. He reportedly says to his jurors if his teaching about the nature of virtue "corrupts the youth, I am a mischievous person." He tells the jury, according to Plato, he would rather be put to death than give up his soul-saving: "Men of Athens, I honor and love you; but I shall obey God rather than you, and while I have life and strength I shall never cease from the practice and teaching of philosophy." If Plato's account is accurate, the jury knew that the only way to stop Socrates from lecturing about the moral weaknesses of Athenians was to kill him.